Today’s post provides evidence of a high degree of dispersion across price categories that comprise the consumer price basket in South Africa. The first figure shows that, since 2008, a large proportion of inflation outcomes for the detailed components that comprise the consumer price basket have been outside the Reserve Bank’s 3 to 6 percent inflation target band. Both the mean and median outcome across very detailed specific components comprising the inflation basket have been above 5% since 2008. The second chart shows that there has been high dispersion for several categories that are highly dependent on tradable products such as petrol (such as transportation), administered prices such as electricity, and some food sub-categories.

High inflation dispersion has implications for the optimal inflation target and the optimal approach to inflation targeting.

Academic studies tend to show that, in an environment with high inflation dispersion, an inflation targeting central bank should focus on controlling the trend growth rate of underlying inflation. This prevents the central bank from over-reacting to temporary fluctuations in inflation from volatility in some sub-components of the inflation basket.

We suggested in an earlier post that the exclusion-based core inflation measure the South African Reserve Bank and market analysts tend to focus their analysis on may not be the best measure to use to inform monetary policy decisions. There are many ways to measure underlying inflation, and we have been arguing for the last couple of years that South Africa needs new underlying inflation measures and inflation models to guide monetary policy. SARB has recently published once-off analysis of alternative measures of underlying inflation, although our out-of-sample analysis raises questions over how reliable such measures are likely to be in practice for informing monetary policy.

High dispersion can threaten monetary policy credibility. Best practice among leading central banks is to explain the economic drivers of dispersion in inflation and the central bank’s approach to addressing such dispersion. The thinking is that such transparency helps to anchor inflation expectations and maintain the credibility of the central bank as an inflation targeter. What the South African debate is missing is structural analysis of the drivers of inflation dynamics and analysis of the implications for the optimal inflation target.

An implication of essential goods like food or electricity driving high inflation dispersion is that monetary policy aimed at reducing inflation in interest rate-sensitive parts of the economy will tend to stifle economic growth in areas that are not experiencing above target inflation.

Lowering the inflation target without addressing such problems would impose large costs on the economy. Given that several government-related inflation components have pushed up headline inflation over the past decade, achieving a lower target would necessitate coordination with the government to address the high inflation driven by administered prices in South Africa.

Footnotes

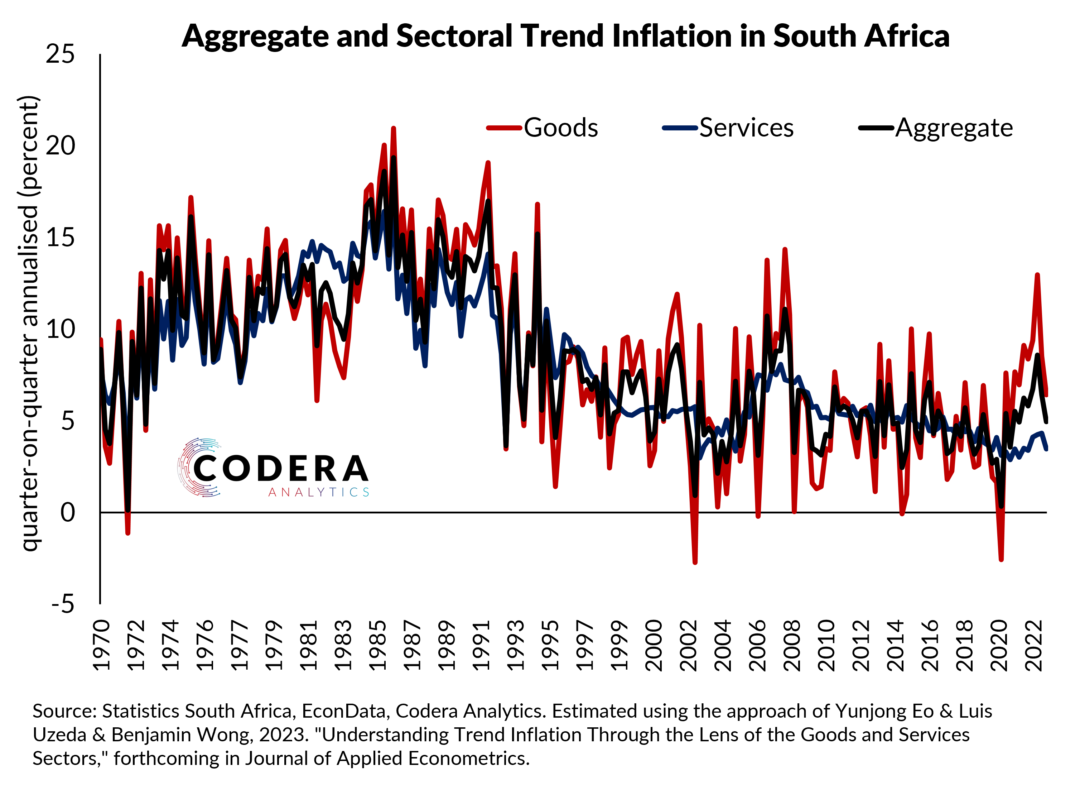

There are several other ways to measure inflation dispersion. Codera’s CPI-common measure suggests that there has been more broad-based inflation pressure since 2019 than implied by the Statistics SA core measure of underlying inflation. We also showed in an earlier post that there has been a widening gap between trend inflation in goods and services components in South Africa.

As far as we are aware, EconData is the only source of historical South African CPI weights back to 1970. Our CPI Weights Module enables analysts to construct alternative consumer price series and analyse historical consumer price pressures. The CPI weights data can also be readily translated to the COICOP classification of the CPI as described in detail in the EconData User Guide. Contact us if you are interested in subscribing to our subscriber-only EconData Modules.

Charts compiled by Oliver Guest