March inflation data for South Africa will be published today. Expect market analysts to immediately make unqualified assertions about what the outcome for core inflation will mean for headline inflation and future interest rates. This post shows that the core inflation measures the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) and market analysts focus their analysis on do not do a good job of predicting inflation. This post also argues that assessing the implications of measures of underlying inflation for monetary policy requires models, since one needs to judge what the economic drivers of underlying pressures are.

A test of the usefulness of core inflation measures is how well they predict future inflation. The charts below compare the out-of-sample predictive accuracy of different core measures, defined as the difference between their 12 month ahead forecasts of headline inflation less the year-on-year rate in headline inflation that was observed fora given month. This shows that all of these measures have historically been poor guides to persistent changes in inflation in South Africa. For example, all three measures completely failed to predict the post-pandemic inflation spike. Over the full sample considered since 2008, the trimmed mean measure has the lowest absolute mean forecast error.

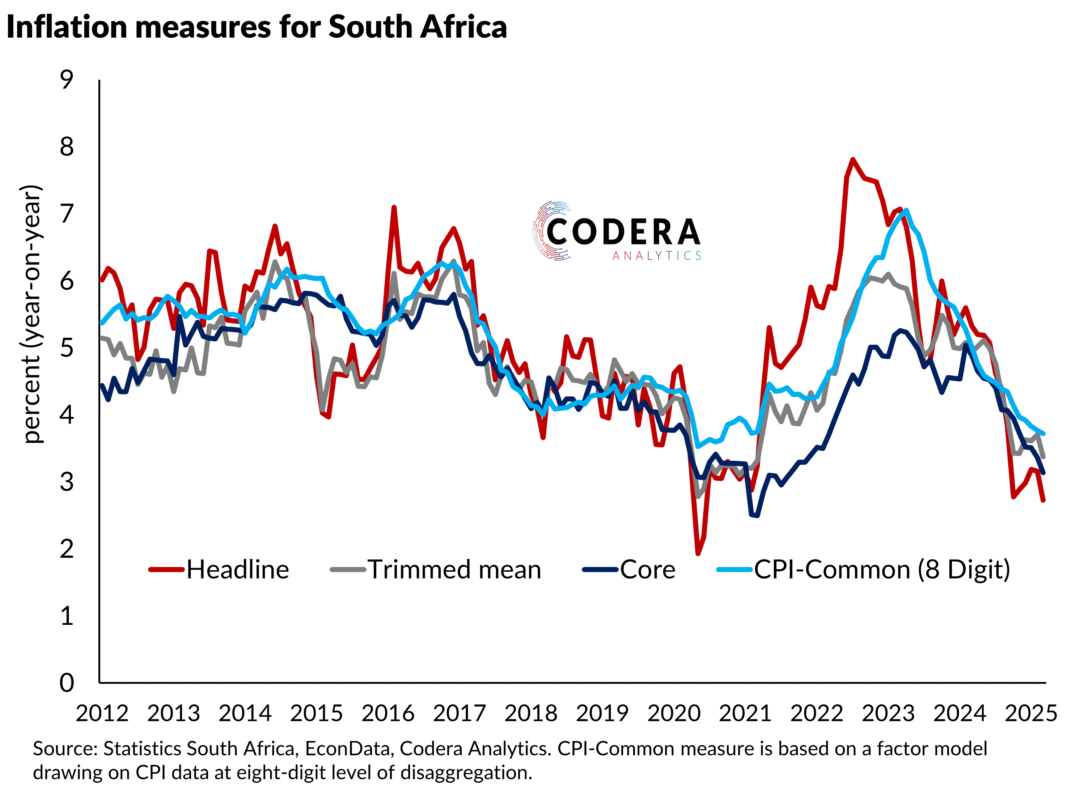

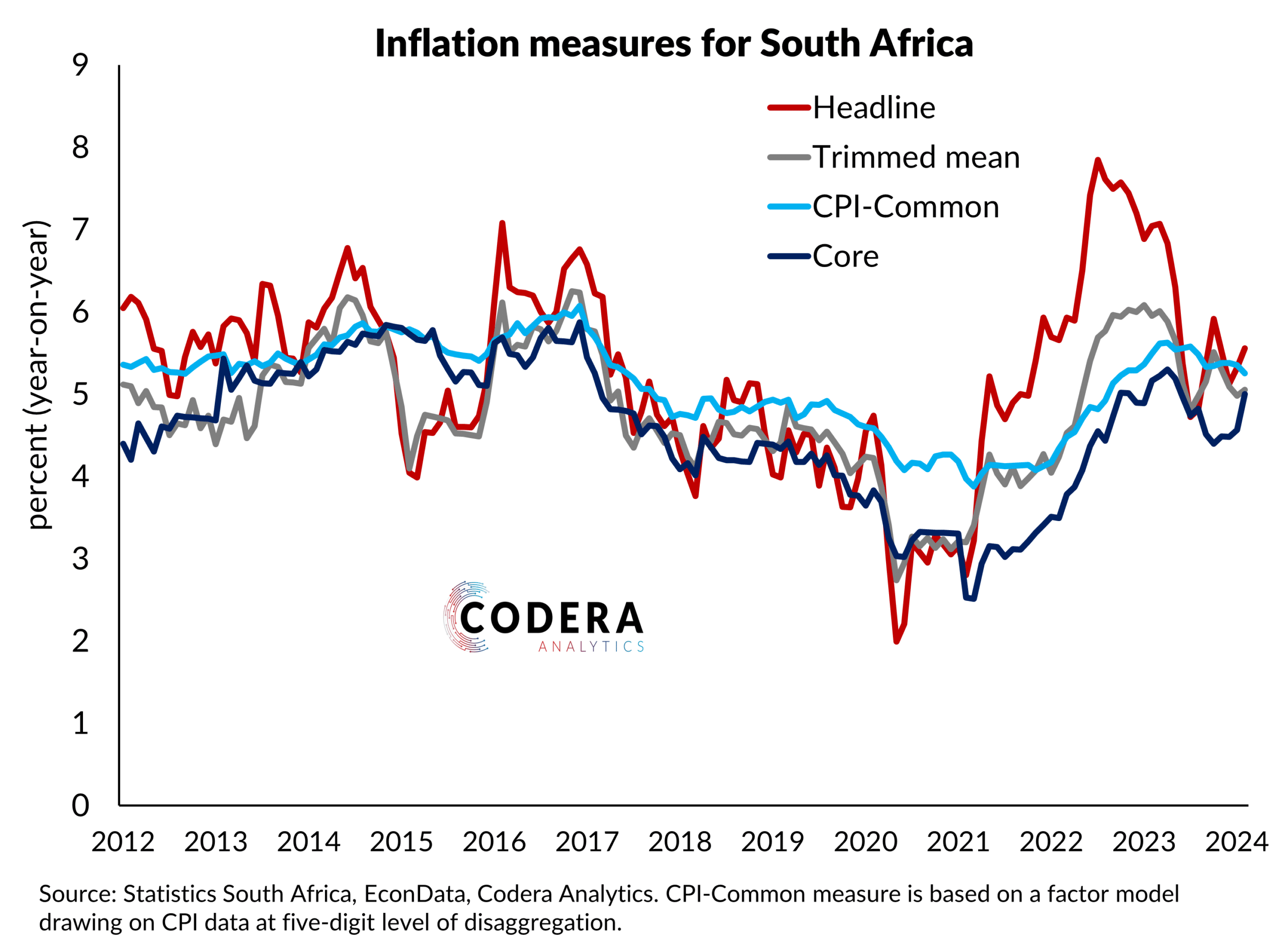

If these core inflation measures are not good predictors of inflation, then what are policymakers to do? One option is to expand the number of measures considered when assessing underlying inflation, particularly incorporating measures that have an economic interpretation. Our CPI-common measure (see first chart) which is based on a factor model of 5 digit level CPI components suggests that there has been more broad-based inflation pressure than implied by the Statistics SA core measure of underlying inflation since 2019. The second chart however shows that our measure does not perform better than the other core measures at predicting inflation. It would be useful to assess how alternative measures, such as measures of cyclically sensitive prices (as we estimated in this earlier paper), might perform.

Another option is to use structural models to interpret the drivers of underlying inflation. Leading central banks use their policy models to interpret business cycle drivers and assess the implications for the stance of policy. It would be useful for SARB to use its policy model to assess the appropriateness of its policy stance and communicate its economic narrative. SARB has not, unfortunately, provided analytical content showing whether the update to its policy model in 2023 has affected its model’s ability to explain inflation dynamics.

In this earlier paper, we showed that a measure of cyclically sensitive prices had a stronger and more stable relationship with capacity pressures than headline (or core) inflation. We also showed that SARB’s preferred output gap measure performed poorly in explaining and forecasting inflation in South Africa, so it would be useful to understand whether the recalibration and updated output gap and core inflation estimates have improved the fit of the model specifications or not.

We also showed in an earlier post how one can estimate trend inflation and use such measures for understanding the drivers of underlying inflation or assessing what an appropriate inflation target might be.

These results suggest that market analysts and policymakers should be careful about making statements about the implications of core inflation outturns for headline inflation in South Africa. This also suggests that new measures of underlying inflation and models of the drivers of underlying inflation in South Africa are needed.