Today’s blog post provides a version of our Business Day article, with extensive links, in which we argue that SA’s geo-economic gamble with China and Russia does not make economic sense.

SA’s geo-economic gamble is not paying off

Data shows shift away from traditional trading partners to Brics group does not make economic sense

Daan Steenkamp and Jacques Quass de Vos

SA’s geoeconomic gamble lies in its growing tilt toward China and Russia in bilateral relations, even as its trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) remain dominated by Western partners. Does the shift away from traditional trading partners towards the BRICS group make economic sense? The data suggests not.

Rising tensions with the US and policy uncertainty already have an impact. South African exports to the US down were down over 20% year-to-year for each of the last three months. And this is before we can measure the impact tariff implementation will have.

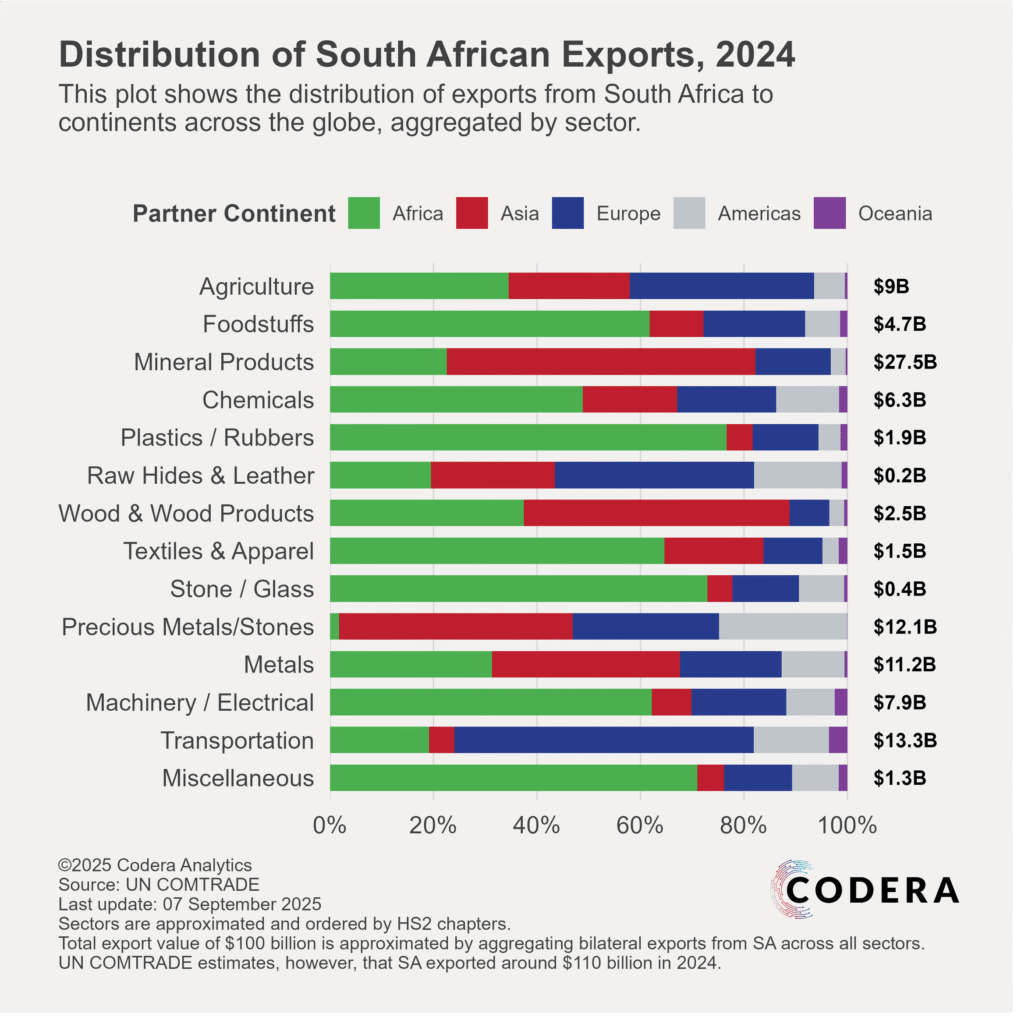

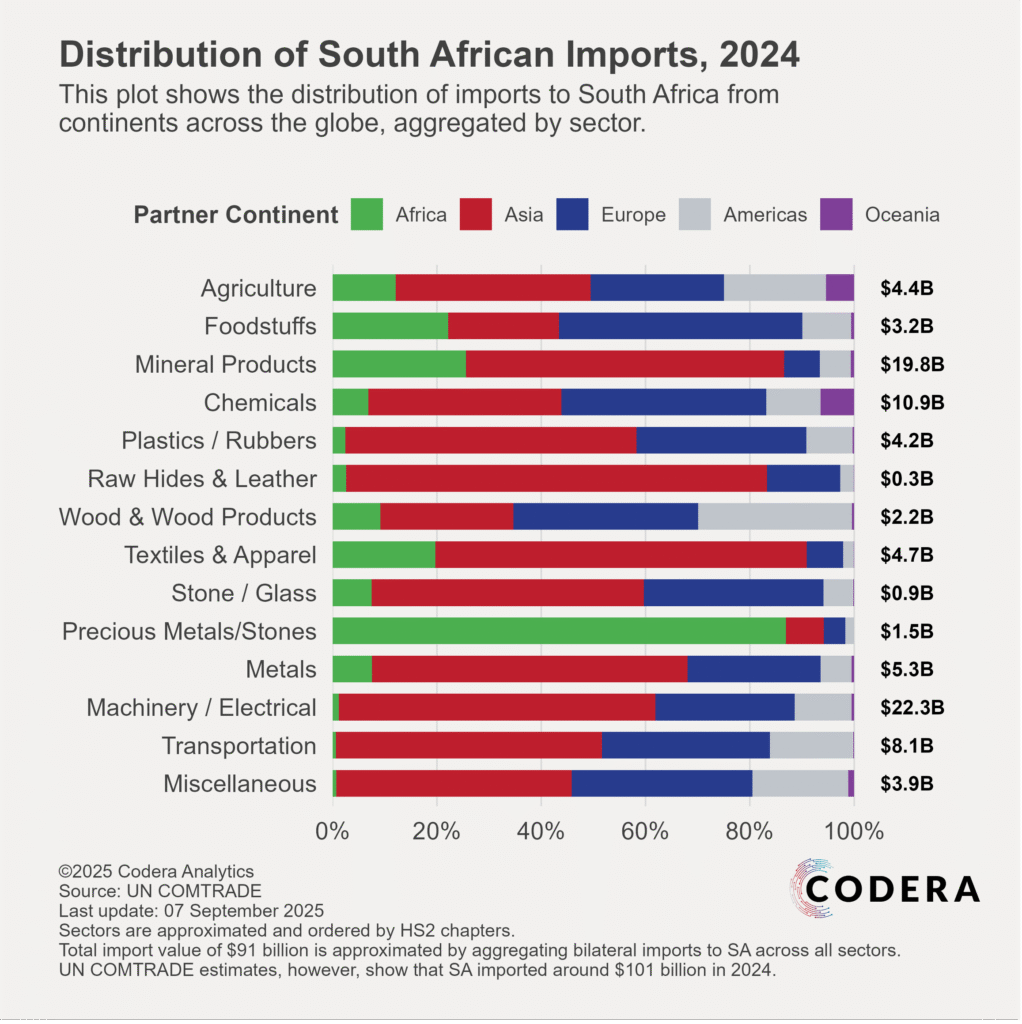

Western trading partners represent around a third of South African exports and imports, while China is SA’s largest individual trading partner. China is a critical buyer of South African commodity exports, representing around 12% of total exports, and produces almost a quarter of our imports of manufactured goods. Russia represents less than 0.5% of our trade.

Despite the attention the BRICS group gets in our international relations, these countries have offered limited export and investment benefits. Together, the West accounts for over 80% of SA’s inward investment, compared to only 5% from BRICS.

SA’s political pivot has occurred against a backdrop of a multi-decade decline in SA’s role in global trade and capital markets. SA’s share of world merchandise trade has declined three-fold over 30 years. Inward FDI has fallen off a cliff over the last decade. In 2023, SA only received around $1750 of foreign investment per person, compared to around $2700 in 2009, before accounting for inflation.

The decline in investment returns in SA have also seen SA firms and households move their investments overseas. Ironically, the value of SA Inc’s foreign assets has soared on the back of strong relative investment returns (think of the performance of Naspers’ global internet investment business) and favourable valuation changes from exchange rate changes (rand depreciation boosting the value of foreign currency denominated foreign assets).

But this likely reflects a weakening of confidence in the SA economy. Since SA imports more than we export, this also raises concern around whether we will continue to finance our current account deficit as easily as it has over recent years.

Apart from decoupling from global trade, SA has experienced a decline in the economic complexity of our exports. Both the Harvard Growth Lab and Observatory of Economic Complexity’s measures of export sophistication show that while fast growing countries like China’s export based has become more diversified and technologically advanced over time, the opposite is true for SA.

It is worth zooming in on the automotive industry, as it receives a large share of the government’s industrial support. A recent SARB working paper by Guannan Miao and Fons Strik shows that SA’s automotive industry uses fewer inputs from foreign upstream industries than many of our peers. SA’s ‘export intensity’ (how much of domestic value added is represented in final foreign consumption of goods or services) and ‘processing’ (the quantity of imports used as intermediate inputs that are subsequently exported) are comparatively low. The paper shows that our automotive industry’s integration is lower than one would expect considering SA’s economic structure, resource endowments and industrial policies.

SA’s trade intensity is low compared economies that have increased per capita income over recent decades: it is only a third of those of countries like Malaysia or Vietnam. Trade intensity is important for productivity growth because trade exposes firms to competition and provides access to a wider variety of inputs, including new technologies. This promotes specialisation, helping firms capitalise on our comparative advantages.

SA does play an important trade role in Africa. But this partly reflects the benefit of the Southern African Customs’ common tariff barriers. SA’s intra-African trade remains underdeveloped relative to its integration into the global economy. Regulatory and border frictions and the deterioration of our rail, road, and port infrastructure have made things harder. Incredibly, SA port activity is still down relative to pre-pandemic levels.

This also reflects deteriorating price competitiveness, driven in part by dramatic increases in municipal rates and tariffs and collapse of government service delivery. Eskom’s standard tariffs have increased at almost 15 % per year since 2008, compared to consumer price inflation of about 5.8 % over this period.

Another important factor has been SA’s increasingly anti-growth regulatory frameworks. The number of laws in SA have more than doubled since democracy, raising compliance complexity and costs. SA is at the bottom of rankings of major developed and emerging markets for regulations that discourage business registration and growth, according to estimates from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Outdated exchange control and investment regulations add sand in the wheels of every cross-border transaction.

Cross-border trade requires networks of quite large formal sector firms. There are several uniquely South African regulations that disincentivise firms from growing. The race-based employment equity quotas that have come into power this month create a strong disincentive for firms to grow beyond 50 people. Likewise, Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) regulations create incentives for firms to keep turnover under R10 million for exemptions from BEE verification.

Export-led economic growth requires that successful firms grow. China’s industrialisation and dramatic income growth was sparked by large export-orientated firms that established supply chain and logistics networks and enabled an ecosystem of smaller specialised firms to emerge and grow.

But as shown by a 2019 World Bank study and recent OECD research, SA’s economy is dominated by large but low output and employment growth companies, with little dynamism from small or medium sized firms. Despite high levels of concentration, with a small number of dominant firms, the correlation between concentration and profit margins is very low in SA, with many high concentration industries experiencing low profit margins.

In part, this reflects the long-term decline in net profit margins in SA from a deterioration in the business environment and the outsized role of government-related corporations or capital intensive recipients of state support.

The consequence has been that SA is deindustrialising, despite the highest commodity prices in more than two generations. Manufacturing’s contribution to output has fallen by around a quarter since the early 1990s, while its share of employment has halved.

Over the long term, productivity is a key determinant of the welfare of country’s population. Trade has historically been one of the main drivers of productivity growth, with global integration supporting rising income per capita in fast growing economies. SA’s weaking integration into the global economy and poor productivity performance threatens SA’s future prosperity. SA’s geoeconomic gamble and misguided industrial policies have not paid off and increasingly risk vital economic links with its major investment partners and the African continent.

Dr Steenkamp is CEO of Codera Analytics and a research fellow with the economics department at Stellenbosch University and Jacques Quass De Vos is an associate with Codera.