Today’s blog post is an unedited version of a Business Day article that presents data on why SA is ranked near the bottom globally in terms of our entrepreneurship rate and argues that the root cause of our economic stagnation is a culture of interventionism.

South Africa stands out among major economies for how few businesses are started and how hard it is to keep a business alive. There is growing optimism that the government of national unity might initiate some economic reforms that might address this. But there is a lot of misunderstanding about what the underlying causes of these challenges are and therefore what to prioritise. It is worth looking at the data for guidance.

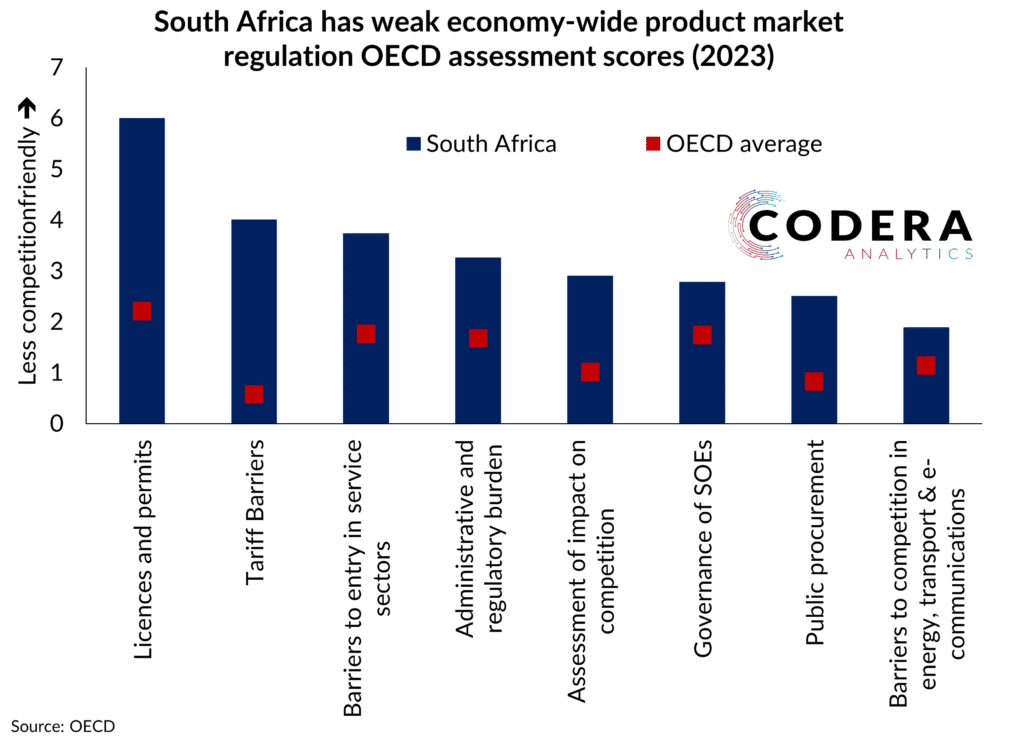

South Africa is ranked near the bottom globally in terms of our entrepreneurship rate, according to the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. The OECD benchmarks of regulatory best practice puts South Africa’s regulatory frameworks as one of the least conducive to global competitiveness. By their assessment, South Africa stands out among major developed and emerging markets for regulations that create barriers to market entry, expansion, and the difficulty of obtaining licences and permits. It is not just that our regulations are not aligned with our peers: the stringency of South African regulations has also tightened over the last decade.

Business owners know exactly what the obstacles are that make things difficult for local entrepreneurs and foreign investors. Yet somehow our problems are still not well defined. This means we cannot quantify the relative importance of factors that are throttling private enterprise in South Africa. We have no statistics on things such as business failure rates, the number of compliance officers at large enterprises, how many documents and emails are required for the average foreign currency transaction, the proportion of government certification institutions that do not respond to client queries, or how much it costs to achieve higher Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment scores.

This undermines efforts to galvanise public support for reforms. It took 17 years for government to allow private participation in electricity generation because the causes of Eskom’s problems were poorly understood, and private sector involvement ideologically opposed.

The same is true of South Africa’s labour market. South Africa stands out globally for its high rate of unemployment. Apart from Apartheid policies, this is a symptom of labour market regulations that raise the cost of employment and incentivises firms to avoid formalisation. Yet there is little political momentum pushing for reforms to address jobless growth.

South Africa’s underlying problem is government insistence on intervening in many parts of the economy. The government’s share of the economy, measured as tax revenues to GDP, has been higher than in other major BRICS economies since 2010 and continues to rise.

Another good example is South Africa’s trade policy. South Africa stands out for its high levels of tariff protection, the extent of government support, our woeful export performance. Export volumes, for example, have been flat over more than two decades. Import-substituting policies have not only failed to promote competitiveness or raise the sophistication of exports, they have also made it difficult for new firms to compete with well-supported competitors and created a lobby that opposes trade reform.

Government’s poor provision of services also make it challenging to run a business. Around 70% of South African firms had generators in 2020, with as much as 50% of manufacturing firms’ electricity being generated by generator, according to the World Bank. The Reserve Bank estimates that load-shedding reduced economic growth in 2023 by almost 2 percentage points.

The SARB’s loadshedding growth impact estimates do not incorporate the contributions from other service delivery-related challenges, such as South Africa’s failing water infrastructure, declining rail and port capability or crime. Regarding the latter, the World Bank estimates that crime costs South Africa 10% of GDP annually. This is big. For 2023, this cost is almost three times government’s total expenditure on healthcare. It is more than implementing a basic income grant would cost.

Policy uncertainty is another important reason for South Africa’s anaemic investment and low business start-up rates. Exchange controls and approval requirements for cross border transfer of intellectual property make it difficult for start-ups to raise capital from foreign investors and discourage even small cross border transactions. This limits integration with the global economy and creation of networks to other economies. The SA Startup Act Movement argues that uncertainty around the treatment of intellectual property and exchange controls are behind an increase in emigration by South African entrepreneurs.

The Employment Equity Amendment Act of April 2023 implies that entities with more than 50 employees will in future need to meet sectoral ministerial equity targets and require detailed annual reporting. Substantial fines for noncompliance are also being considered. These regulations not only create large compliance costs but incentivise firms to stay small. Discouraging growth weighs on productivity and efficiency by reducing economies of scale and inhibiting job creation.

Small and medium sized businesses account for over two thirds of employment, so growth of small business is crucial to raising welfare and dealing with South Africa’s socio-economic challenges. The National Development Plan recognises this but has been short on tangible reforms to cut red tape.

Project Vulindlela is a praiseworthy initiative between the Presidency and National Treasury that is seeking to improve regulatory efficiency and reduce compliance costs. Its focus is on addressing electricity supply constraints, fixing water and rail infrastructure improvements, improving our visa system and accelerating license processing. There are signs of progress in many of these areas. But this is still focused on treating the symptoms of South Africa’s anti-growth disease. A more ambitious set of structural reforms is needed to align South Africa to global regulatory best practice.

The lifting of restrictions on private sector participation in electricity production has been tremendously successful in helping to resolve our electricity crisis. It is time that the government of national unity unleashes the private sector to deal with other of our societal challenges.

At the same time, it is time to leash the parts of government and state-owned enterprises that are making things actively worse. Non-performing state institutions need to be restructured and wages tied to productivity. Last year’s Harvard Growth Lab report argued that a shift to merit-based employment in the public sector and relaxation of preferential procurement rules are key to removing barriers to growth. Something else that is well overdue is a comprehensive set of regulatory impact assessments across the areas where South Africa ranks poorly globally. Policy decisions and prioritisation of structural reform plans must be empirically based.

The underlying reason for South Africa’s poor growth and high unemployment is interventionism. Many businesses that are recipients of state largess are complicit in perpetuating this. The government needs to shift to evidence-based regulations and commit to getting the basics right.

Dr Steenkamp is CEO at Codera Analytics and a research associate with the Economics Department at Stellenbosch University.