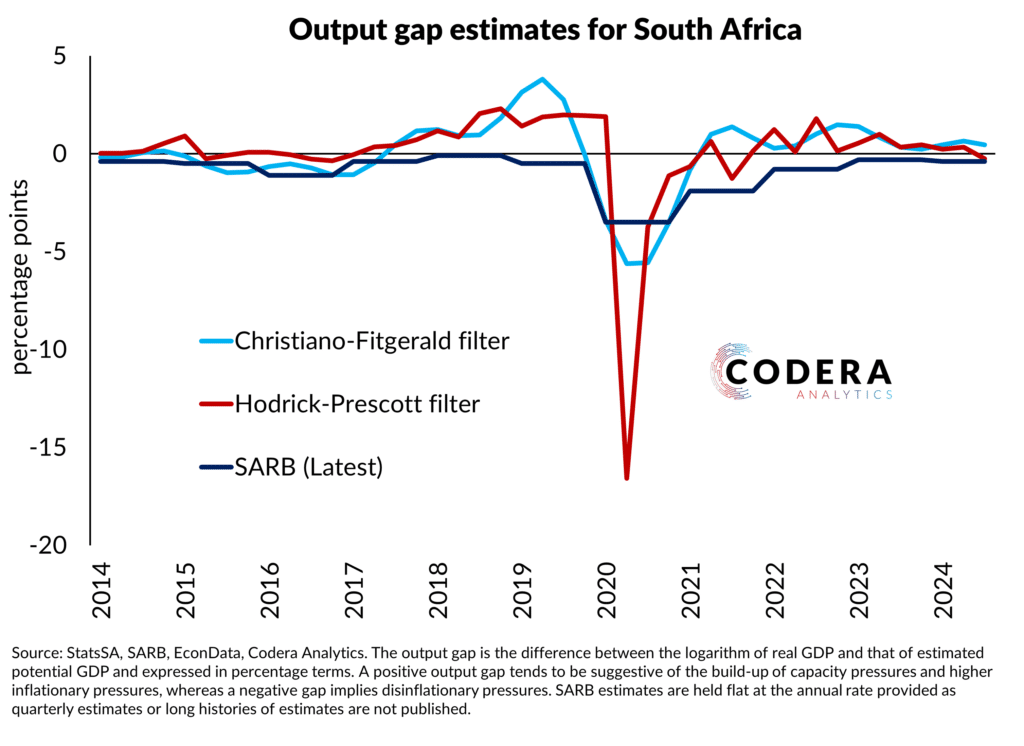

The output gap (a measure of economic slack) is estimated by the SARB to assess the state of the economy and the impact of capacity pressures on the inflation outlook. The SARB’s estimates have been consistently negative since the global financial crisis (GFC) (and remain negative in their projections, albeit closer to zero). SARB’s estimates imply potential at 1.3% in 2024 and 1.4% in 2025.

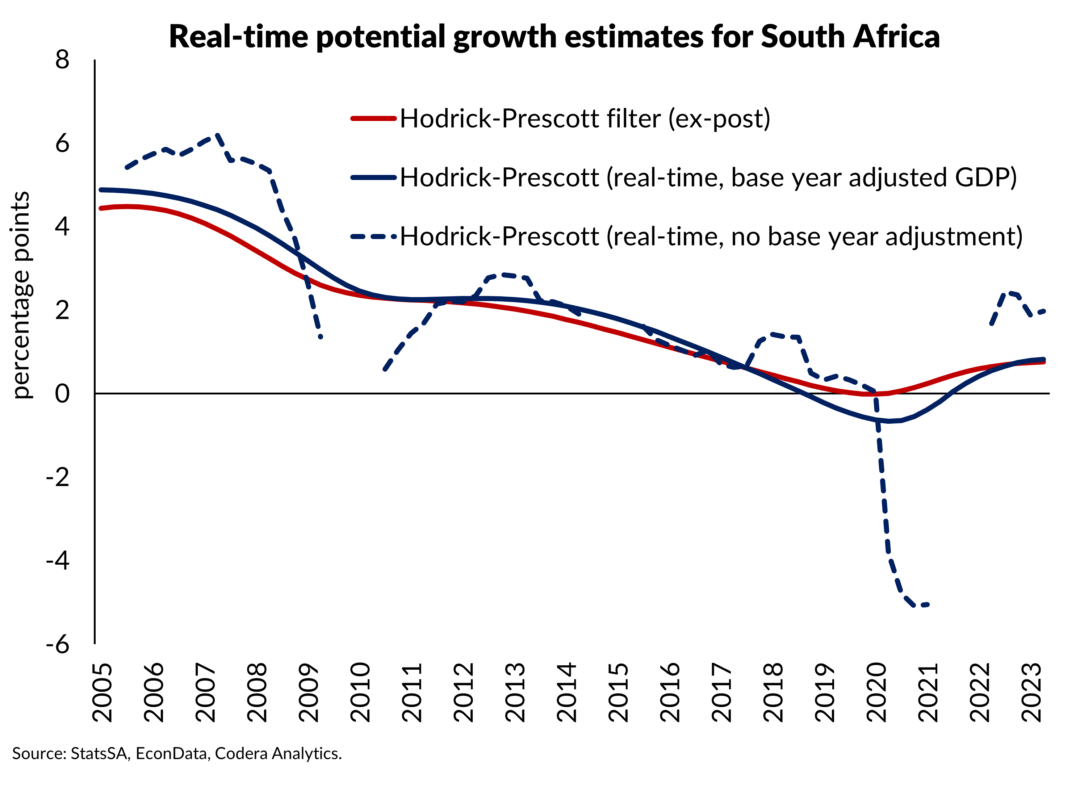

Simple statistical filters, such as the Hodrick-Prescott (HP) and Christiano-Fitzgerald filters, on the other hand, imply the existence of a positive output gap before Covid-19 pandemic and for most of the period since 2022. The output gap estimates from these filters imply that potential growth has been falling (to below 1%, see an earlier post here). These estimates suggest that there have been larger capacity pressures pushing up inflation than SARB has assumed.

It is worth reposting some of the points made in an earlier post on this topic. The first problem with SARB’s systematically negative output gap estimates for over 14 years is that the statistical definition of an output gap implies that estimates should be approximately mean zero over the long term. The statistical filters, such as those presented here, are approximately stationary.

When used in a model such as SARB’s QPM forecasting model, the output gap is also an equilibrium concept, which has a requirement that deviations of GDP from potential should eventually be corrected over time. While SARB has generally been projecting such, when you look at its historical estimates, they have remained negative over the post-GFC period.

This has implications for the economic narrative of the SARB. Chronic negative output gaps are indicative of persistent economic slack requiring policy accommodation. In the context of QPM, such output gap estimates create problems for forecasters. If GDP does not converge on potential, models will either produce systematically biased projections or forecasters will need to make incredible (in its original Latin sense, implying ‘unbelievable’) assumptions about the shocks that are affecting the economy.

As I have previously argued, SARB, like other central banks, originally interpreted the COVID-19 pandemic as a massive demand shock, ultimately under-estimating the delayed inflationary impulse from supply shocks associated with economic lockdowns. Since then, SARB has revised its interpretation of the economic impact of the COVID pandemic, communicating in the October 2024 Monetary Policy Review that it now assumes that the pandemic was predominantly (75%) a supply-related shock.

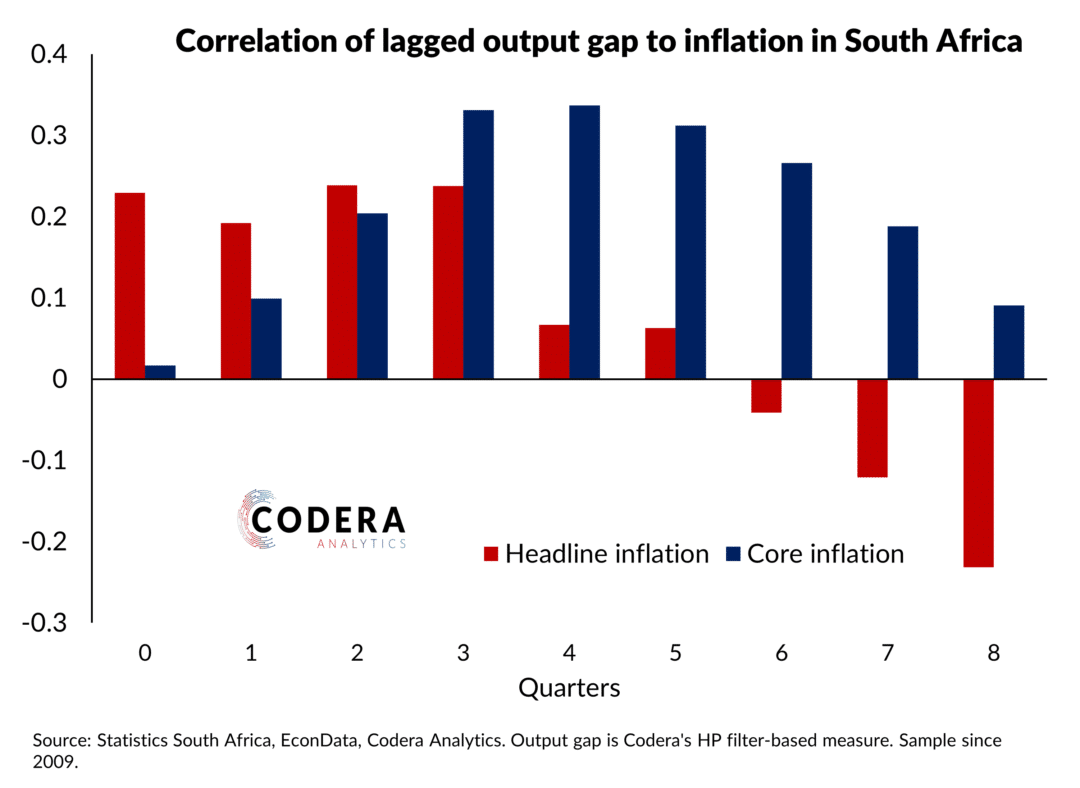

Another test of the credibility of output gap estimate is whether they are useful in explaining current GDP and inflation (i.e. the state of the economy) or forecasting future GDP or inflation. We showed in an earlier paper that SARB’s output gap estimates performed poorly at predicting GDP growth in models specified in line with SARB’s QPM. Output gap measures that were not persistently negative post-GFC performed best at predicting inflation and GDP growth. Our analysis in this recent post also suggested that the pass-though to underlying inflation of capacity pressures peaks may be very different from what SARB’s estimates imply. Over time, SARB has recognised that its historical potential growth estimates have been too high and have progressively lowered them. Our analysis suggests that SARB will need to revise its estimates in 2025.

Footnote

Note that the HP filter is a commonly used statistical approach for output gap estimation. The problem with simple filters such as the HP is that they are not well suited to interpreting the economic impact of the COVID shock. That said, they are useful benchmarks to compare more sophisticated approaches against. For a real-time comparison of the HP filter see this earlier post.