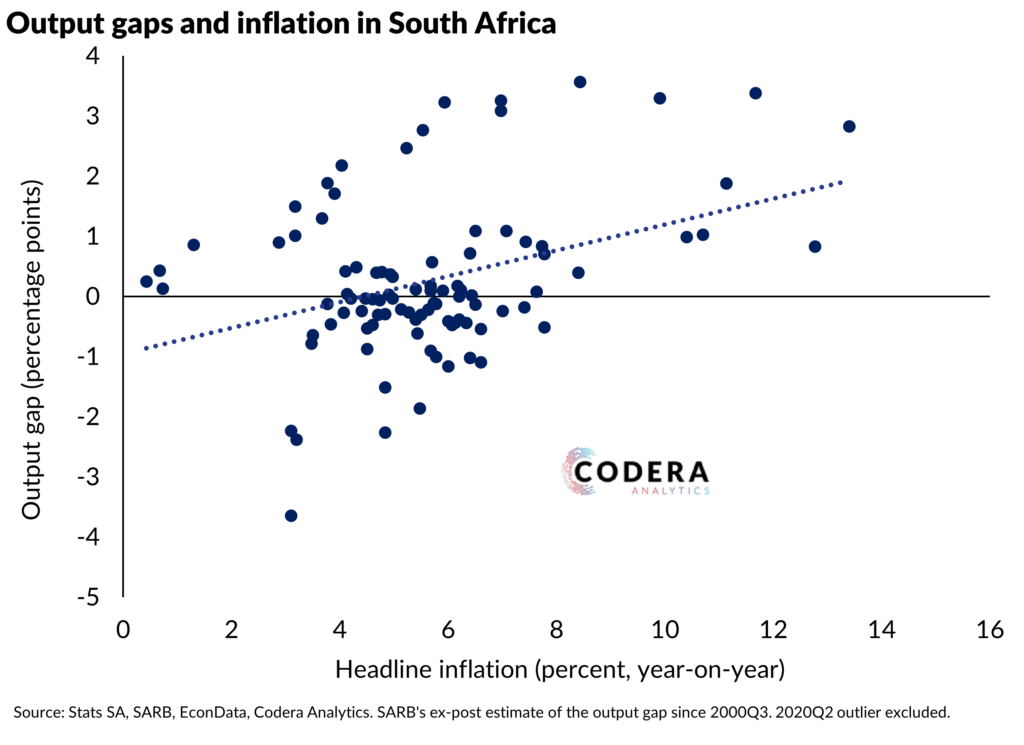

In an earlier post, we showed that a positive output gap—where actual economic output exceeds potential—typically leads to rising inflation as demand-driven pressures push up prices. This relationship, aligned with concept of the Phillips Curve, suggests that when the economy operates above capacity, businesses pass higher costs onto consumers, reinforcing inflationary trends.

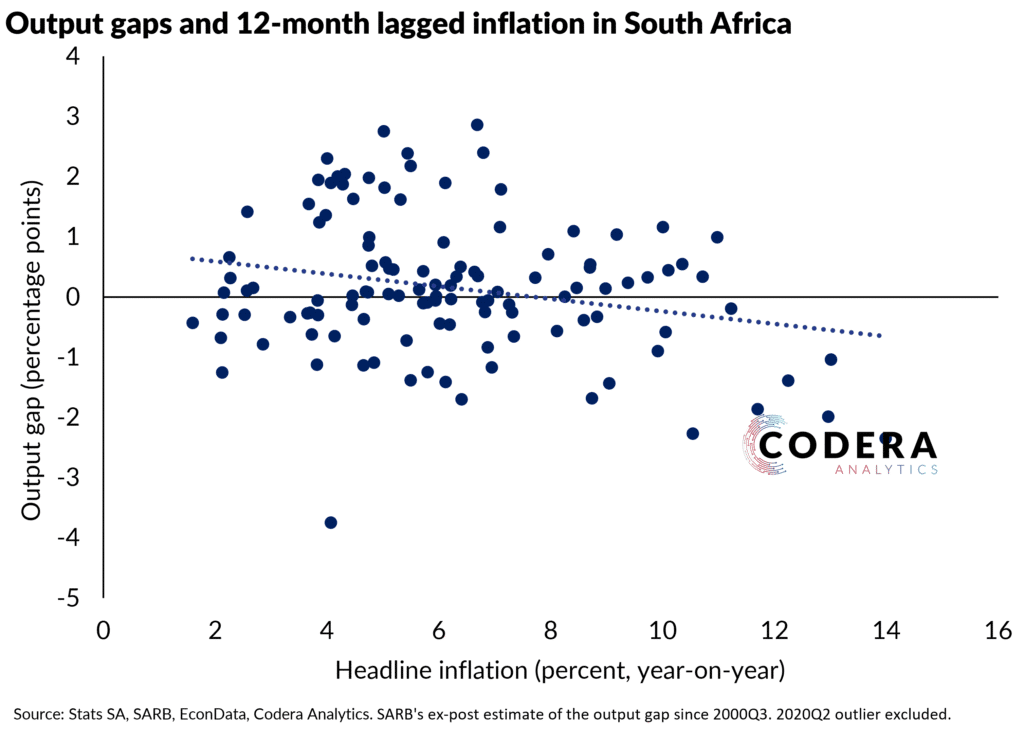

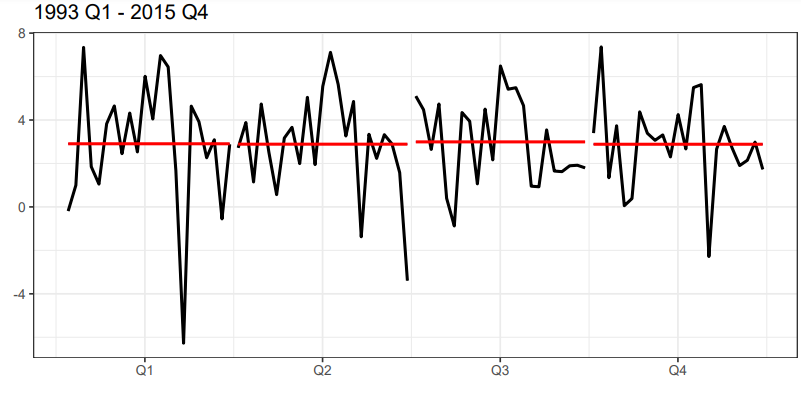

In today’s post, we repeat the analysis, but this time drawing on the SARB’s own ex-post (i.e. revised) estimates of the output gap. SARB’s estimates produce a stronger relationship since 2000Q3 than those of a statistical filter suggest for the contemporary relationship between the output gap and inflation. But SARB’s estimates imply no relationship between the output gap and subsequent inflation, when a statistical filter tends to suggest a slightly stronger relationship. This is consistent with an earlier paper that SARB’s output gap estimates performed poorly at predicting GDP growth in models specified in line with SARB’s QPM. Output gap measures that were not persistently negative post-GFC performed best at predicting inflation and GDP growth. Our analysis in this recent post also suggested that the pass-though to underlying inflation of capacity pressures peaks may be very different from what SARB’s estimates imply. Over time, SARB has recognised that its historical potential growth estimates have been too high and have progressively lowered them.