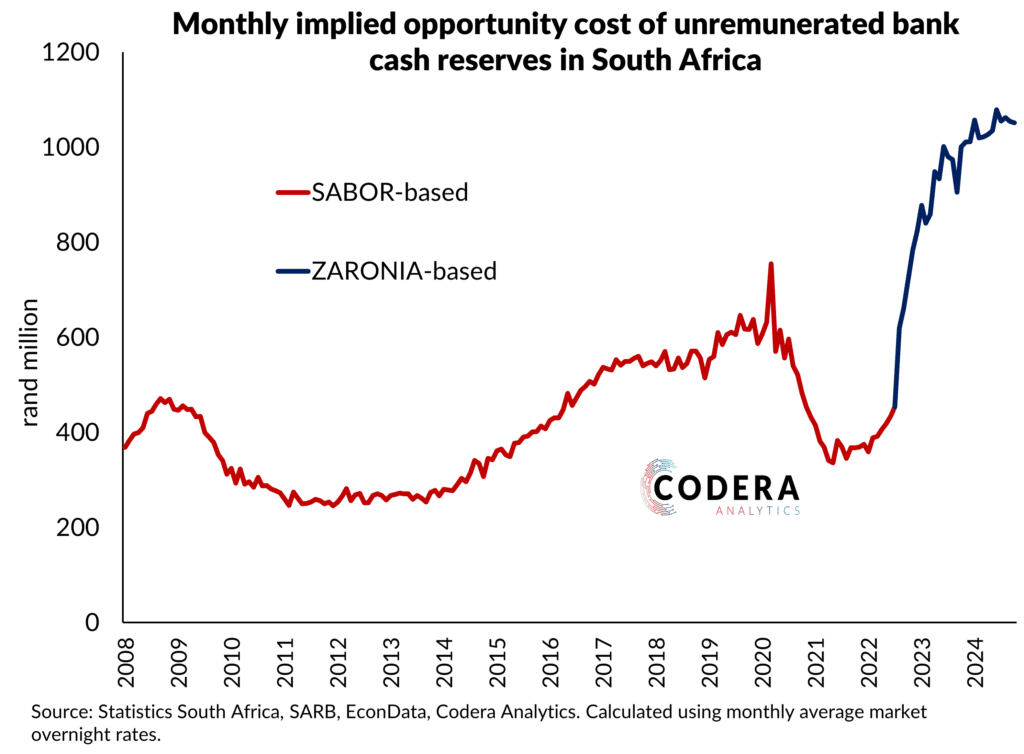

In South Africa, registered banks are required to keep 2.5% of their liabilities with the SA Reserve Bank (SARB) without receiving interest. This represents a form of financial repression – affecting market interest rates and the cost of debt. As it is a tax on banks, it is likely that the costs are borne by bank depositors and borrowers. If this discourages lending, it may weigh on investment and economic growth.

By not paying interest on reserve balances, the SARB reduces the cost of maintaining its monetary base. In this way, the policy serves to increase SARB’s seigniorage revenues.

In this post, we estimate the implicit cost to the banking sector of these requirements and the seigniorage revenues that they produce for SARB. The opportunity costs represent around 5 percent of banks’ average monthly net interest income.

It is also a lot compared to SARB’s seigniorage from its monopoly in production of notes and coins. Over the last year, we estimate that the opportunity cost to banks has been about R12.5 billion. SARB does not publish seigniorage data, but we estimate that these have been approximately R80 billion (before production and distribution costs) since 2008. This is lower than the total implied revenues from unremunerated reserves, which we estimate have been around R100 billion.

Given the recent shift to a surplus-based monetary policy implementation framework, unremunerated reserves are no longer required to create a liquidity shortage in the banking system for the SARB to ensure influence over interest rates. As we noted in an earlier post, the decline in the use of cash has meant that SARB’s expenses with respect to money production have actually exceeded potential seigniorage revenues. This is one reason the SARB may be reluctant to remove unremunerated reserve requirements, even if they are no longer required under our new policy implementation framework.

Footnote

On the one hand, these estimates likely underestimate the benefits SARB receives from imposing unremunerated reserves as these extra resources create an opportunity for it to earn higher returns on its asset portfolio. This is difficult to quantify given the lack of detail SARB publishes about its balance sheet. On the other hand, we have not estimated the cost of maintaining an excess reserve regime, which may be higher than maintaining a money market shortage.

There are also other features of South Africa’s regulatory landscape that have financial repression-type of effects. Prudential regulations aimed at promoting financial stability require banks to hold sovereign debt on as high-quality liquid assets. The Government Employees Pension Fund administered by the Public Investment Corporation also has a mandate to purchase sovereign debt. Lastly, foreign exchange controls and regulation 28 that limits offshore investments of retirement funds create home bias in portfolio allocations. As we have argued before, there is evidence of crowding out of private sector access to capital (here and here). A good postgraduate research project would be to estimate the extent to which these policies have artificially reduced the cost of sovereign borrowing and interest rates and the diversification opportunities for private investors.