In today’s blog post, we repost an unedited version of our Business Day article in which we argue that there is a need for greater transparency from the Reserve Bank. We also provided more technical detail about our forecast comparison between the Reserve Bank and other central banks in an accompanying blog post.

BYRON BOTHA AND DAAN STEENKAMP: Reserve Bank could do much more to increase transparency

Flipside of SA central bank’s independence is that it has a lot of discretion in its decision-making

No one’s projections are ever likely to be perfectly accurate. But since all sorts of important decisions are taken based on expectations of South African Reserves Bank (SARB)’s decisions, people need to rely on the process the SARB uses to arrive at its projections. The future is unknowable, so of course, mistakes will be made, which is why transparency around how predictions were made is so important.

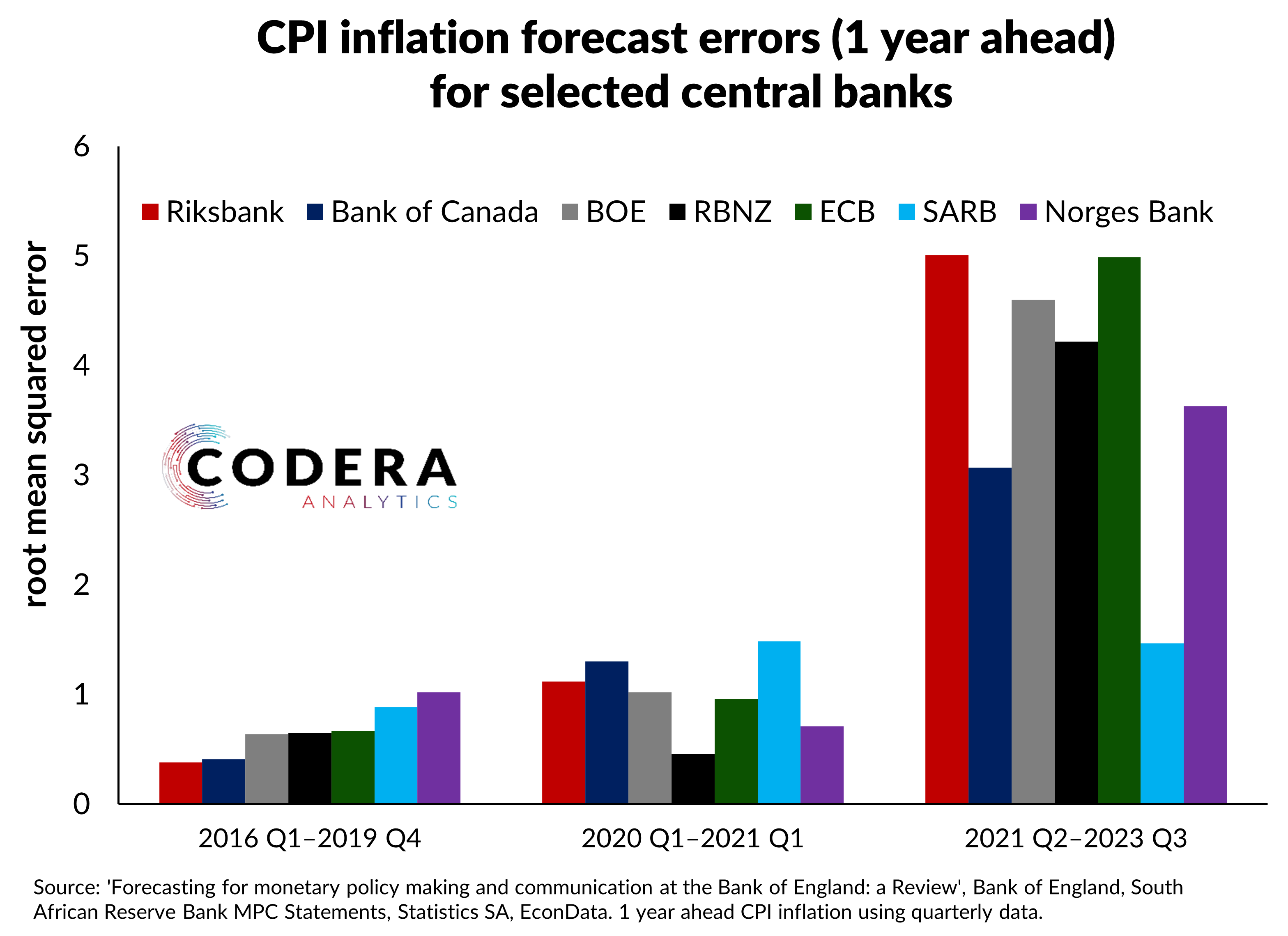

In ‘How Reserve Bank’s forecasting fares in uncertain times‘ the SARB asserts that its forecasts have been more accurate than the International Monetary Fund (IMF)’s estimates for South Africa and more accurate than the forecasts of the Bank of England, European Central Bank and US Federal Reserve Bank for their economies. Our research suggests that SARB forecasts comparisons were not correct. We raised the issue with the SARB but did not receive clarification.

In the chart below we compare SARB’s published projections from all Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) Statements between 2016 and 2023 to forecasts of other central banks from the Ben Bernanke review of forecasting by the Bank of England. Contrary to SARB’s assertion, we do not find that SARB’s inflation forecasts have been more accurate than the major central banks it compared itself to since 2016, even though it performed well since 2021. This comparison is only possible for inflation as the SARB does not make quarterly forecasts of GDP available. However, the GDP forecast errors presented by SARB in the article are much lower than presented in our pre-COVID study of SARB forecast errors published in the South African Journal of Economics. South Africa experiences more economic volatility than major advanced economies, so it is not surprising that is harder to predict macroeconomic outcomes for South Africa.

In a complex, uncertain world forecast errors are inevitable. Whether forecast errors might do damage to an institution’s credibility depends on whether policymakers demonstrate that they understand the factors behind these errors and incorporate what they have learned in their judgements about the risks to the outlook. This means that transparency around monetary policy deliberations and clear communication are crucial to ensuring the market can assess whether the central bank’s judgements are reasonable and that it is credibly committing to its policy target. Unclear communication of its judgements and poor-quality analytical outputs risk weakening the Bank’s perceived credibility in the eyes of market analysts and the public.

Is the SARB sufficiently transparent? The vast academic literature assessing central bank transparency stresses, amongst other things, the importance of publishing projections, alternative scenarios, or qualitative and quantitative assessments of the balance of risk around projections, and periodic publication of external reviews. SARB does not publish quarterly projections for its policy rate or alternative scenarios, nor has it published its recent external model review.

A few technical tweaks in how the MPC communicates its decisions would go a long way to improving the public’s understanding of its policy stance. Being more transparent about the information used to make decisions, its underlying assumptions, and the process by which decisions are reached allows external parties to interrogate whether SARB’s decisions are credible and its modelling and forecasting practices fit for purpose.

The real problem with MPC communication is that it does not communicate its policy stance through its projections, with its decisions sometimes diverging from their published policy rate forecasts that accompany a decision. When words and deeds do not align, it undermines the MPC’s credibility.

There is widespread agreement that the SARB’s current MPC has served South Africa well. But weakening monetary policy credibility would have real implications for the economy. If SARB’s credibility weakens, shifting to a lower inflation target, as the Governor prefers, would imply higher interest rates for longer and therefore a higher cost in terms of growth and employment.

The SARB is a major data provider and could do a lot more to democratise access to public domain data. Consider the banking data SARB publishes. Though SARB publishes detailed bank-level balance sheet statistics, it does not make bank-level regulatory compliance data available. This conflicts with the spirit of the Basel III principle of market oversight.

The flipside of SARB’s independence is that it has a lot of discretion in its decision making in how it implements monetary policy, regulates banking and insurance, manages foreign exchange, and approaches financial surveillance. Discretion, when not accompanied by policy transparency, opens the door to political interference or leaves the institution vulnerable to rogue decisions by future governors. A recent example is the experience of Turkey, which has seen very fast inflation and currency depreciation because of political interference. South Africa has experienced political interference into macroeconomic governance before, with the firing of Finance Minister Nene in 2015.

The SARB is not transparent about many aspects of its other policy frameworks or the governance processes surrounding them. Take foreign exchange reserve management. In this area, leading central banks publish policy documents detailing the goals of their framework, their operational targets, as well as periodic assessments of the appropriateness of policy implementation. Is SARB’s foreign exchange framework appropriate, given South Africa’s particular macroeconomic risks? How well has SARB managed the Gold and Foreign Exchange Contingency Reserve Account (GFECRA)? One cannot evaluate such questions because of the limited information SARB publishes about its framework or how well it has stewarded the portfolio it manages on behalf of South Africans. With monetisation of some of the GFECRA balance recently announced, it will be important for the SARB to demonstrate that it appropriately sterilized the distribution of these funds to government and neutralised the impact on interest rates. The SARB must improve the transparency of its data reporting to demonstrate that such transfers avoided undermining South Africa’s monetary policy framework and the solvency of the central bank.

The SARB has tremendous powers and operational independence. Transparency and governance frameworks are important to keep unelected technocrats accountable. The SARB must make enough information available and expose itself to periodic public external review, so that South Africans can be confident that it is competent in its exercise of its duties and pursuing policy in the best interests of our society.

Botha is CTO of Codera Analytics. Dr Steenkamp is CEO of Codera Analytics and a research fellow with the Economics Department at Stellenbosch University.