Today’s blog post is an unedited version of a Business Day article in which we present a deep dive into mining patent data and raise concerns around investment in innovation and technology in one of South Africa’s areas of international comparative advantage.

Jan-Hendrik Pretorius, Pietman Roos, Johan Hanekom and Daan Steenkamp

Innovation is an unappreciated leading indicator for industry health decades down the line. We overestimate how quick it will take for a technology to be introduced, but underestimate how big the change will be.

This is self-evident in the tech economy, but the converse is also true; a lack of innovation leads to stagnation as the cost-structure prevents operators from keeping up with changing demands. In 2025, air travel is as uncomfortable and unprofitable as it was ten years ago because the technical advances over the decade have been minimal. Closer to ground, the over 600 000 observations of South African patent data available since 1918 would suggest that the prospects for the local mining industry is similarly underwhelming.

Technical innovation and economic activity is the age-old chicken-or-egg dilemma for theorists. A country (or industry) that is prosperous has the available resources to invest in research and development, and technological improvements tend to lead to productivity gains. In this regard, patent registrations are a common proxy for the extent of innovation.

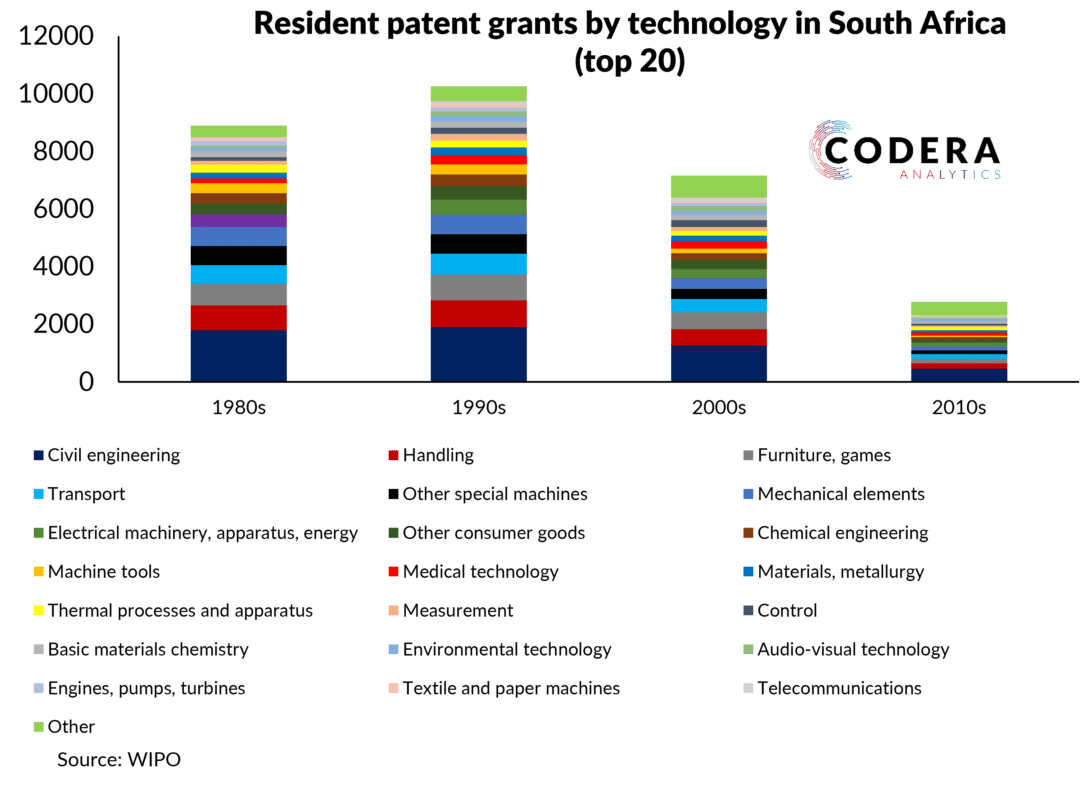

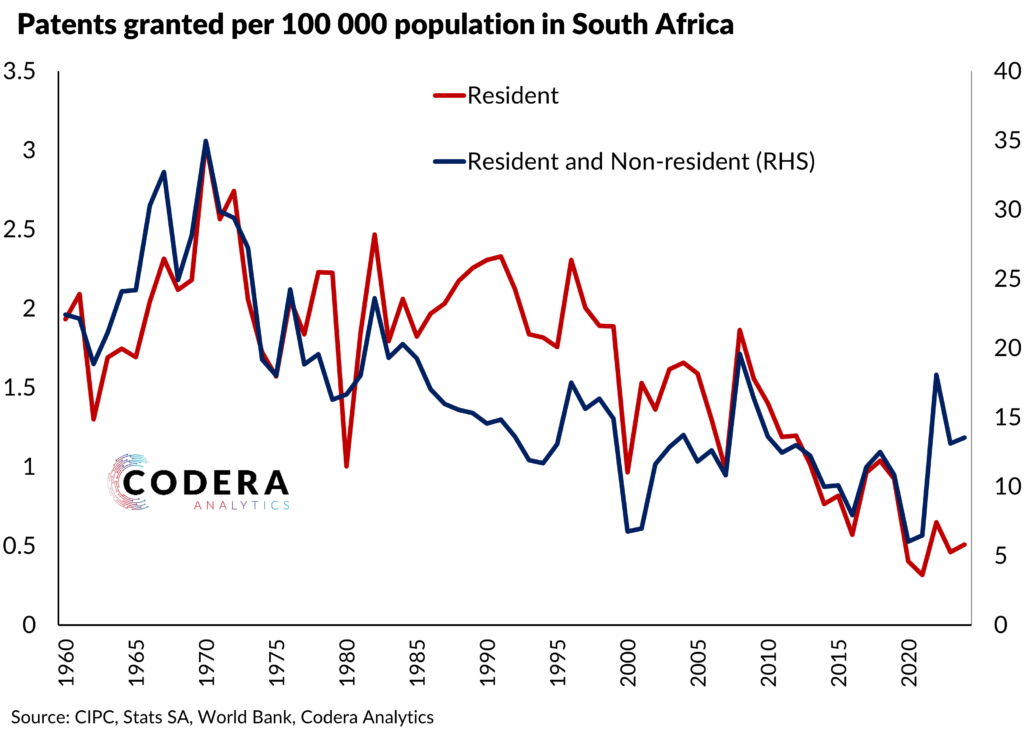

Across industries, the number of patents registered per capita has risen dramatically since the 1980s in many developed countries, and particularly from China. But in South Africa there has been a dramatic decline, particularly for patents registered by residents, as opposed to foreign persons registering in the country. South African per capita patent registrations are down from 3 patents per year by South Africans per 100 000 people in 1970 to around 0.5 in 2024. Even including patents by non-residents, which have risen a lot over the last two decades, total patents granted per 100 000 people is down from 35 to below 15 over this period.

Even though we are very much aware of the scale of technological change and how it can change our lives, South Africans are becoming less inclined to either do the R&D and/or register patents.

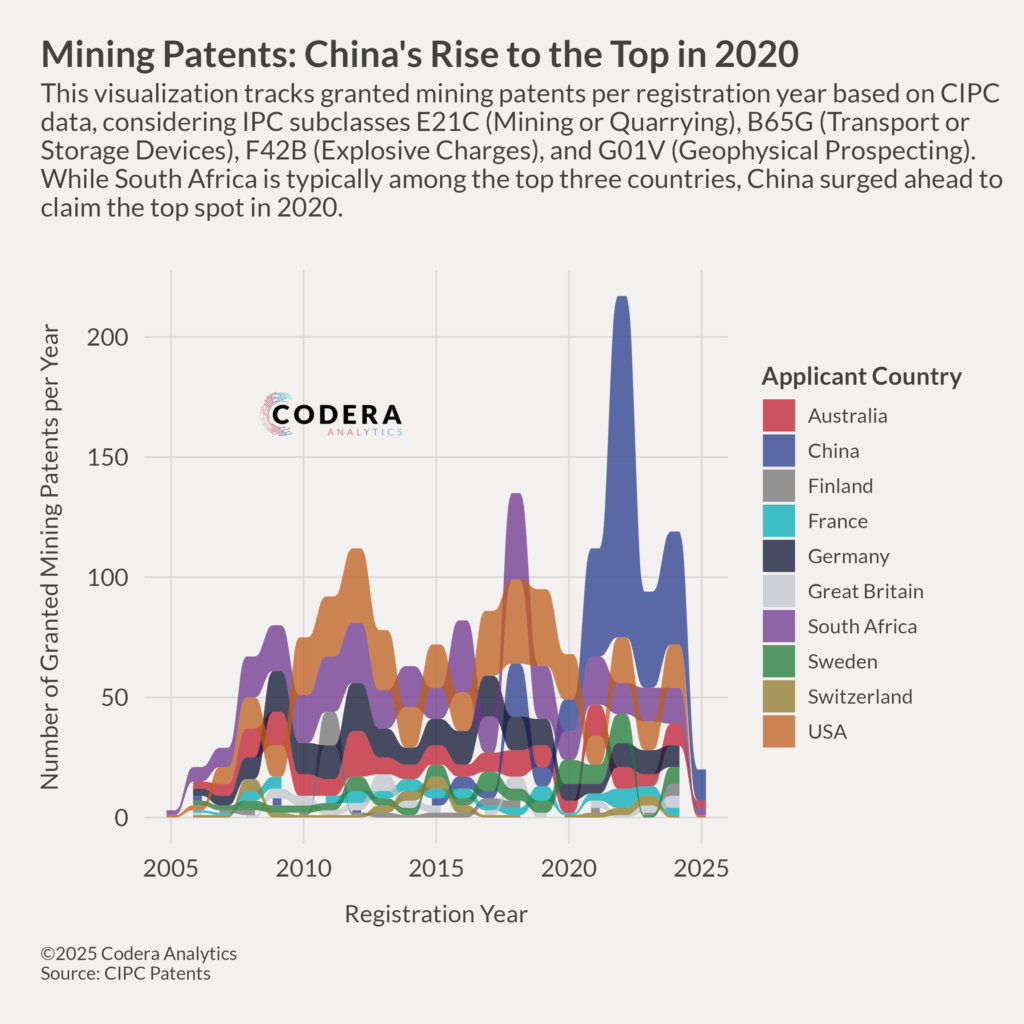

Similarly, the signs are not encouraging for South African mining. Since 2005, when detailed CIPC mining patent data is first available, there have been just short of 2000 patents granted in mining in South Africa, but over 80 percent of these being filed by non-residents. As shown in the chart, South Africans have only registered 346 mining patents in the last 20 years, compared to 367 from the US and 347 from China.

South Africa’s contribution to global mining innovation has also declined dramatically. We estimate that South Africa’s share in global mining patent registrations has fallen from around 10% in the mid-1990s to just over 4% in 2024. South Africa’s share of global mining patent applications is down to only 1% most recently.

When drilling deeper into South African patents, it emerges that a growing share of South African mining patents are defensive in nature – being registered by foreign persons to ensure no infringement occurs locally, while many of the remaining local patents are refinements of earlier innovations. Many of the technologies used in mining in South Africa are also owned by multinational mining companies that have either shifted their headquarters offshore or been acquired by foreign firms.

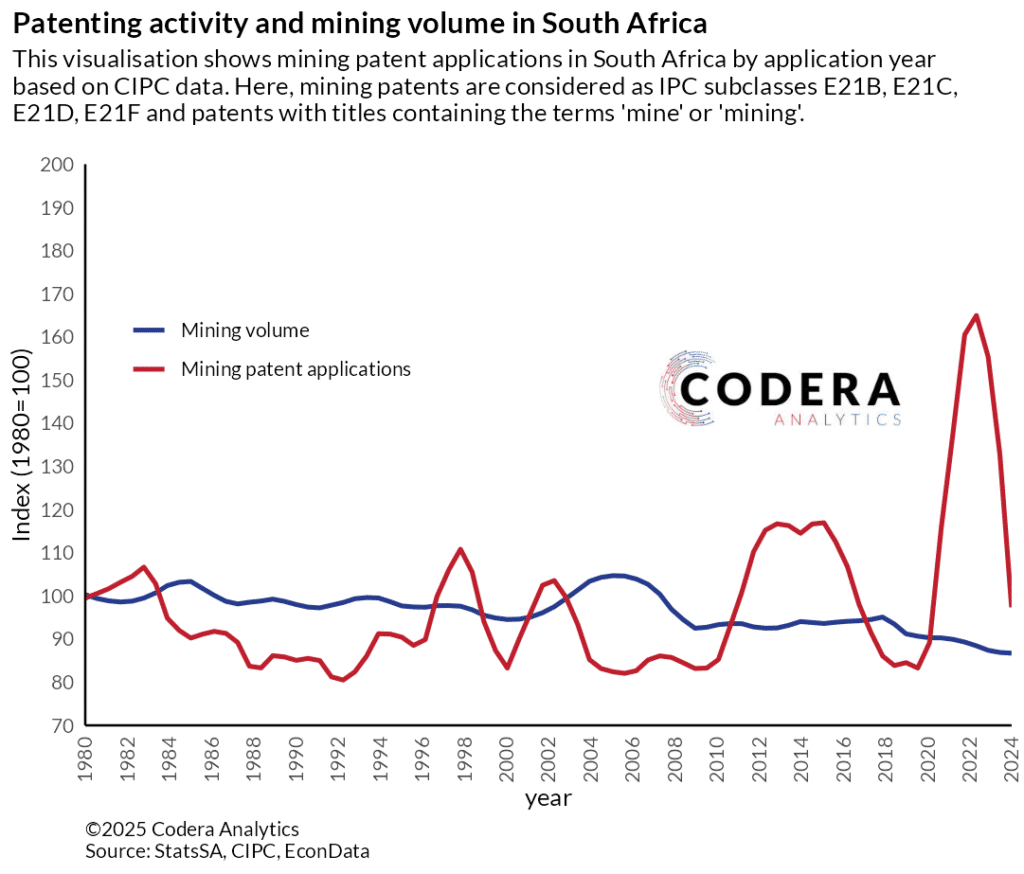

South Africa’s role in global mining has been under pressure for many decades. South Africa’s contribution to global gold production, for example, has fallen from almost 80% in the early 1970s to below 5%. The volume of overall mining production in 2024 was lower than in 1980. This, during a period of phenomenally high commodity prices compared to earlier decades, where countries such as Australia, China or the US have responded by increasing production. Unfortunately, South Africa has failed to take advantage of this income windfall.

Production of metals such as gold and platinum after more than a century does become trickier and more expensive as shafts must be deepened, which tends to weigh on productivity. Estimates of total factor productivity growth have been negative in mining for more than a decade. But loadshedding and policy uncertainty (such as over licensing and mineral rights) have played a key role in the industry’s investment drought and stagnant output.

The irony of South Africa’s earlier prominence in mining, and the crucial role it plays in the economy, is that it is an outlier among South African industries for how small government support and incentives relative to turnover. Across industries, South Africa also lags significantly in research and development prioritisation compared to high productivity economies and has a relatively low number of researchers per capita compared to major emerging markets.

Far from us to critique mining operators for their level of ingenuity, it is safe to say that the workshop in each mine in South Africa hides some interesting innovation which the creator or company never thought to register. That is exactly the policy angle of our patent research: the net effect of government policy is to actively discourage investment in creation of intellectual property in South Africa. Evidence of actual innovation and improved competitiveness should guide industrial policy decisions.

It is not as if South Africa’s industrial policy is a wilting wallflower, ignored by energetic politicians. In fact, you will struggle to find an industry, be it auto, film or even hospitality, that is not somehow included in industrial policy. But the duration and scope of the intervention is a clue as to its efficacy, if everything has always been prioritised then nothing has been prioritised. South Africa’s most recent National Development Plan, which is almost 500 pages long, does not even mention the words ‘intellectual property’ or ‘patents’.

Over the long term, productivity is a key determinant of a country’s per capita income. Low investment in intellectual property creation and declining technological intensity of production threatens the economy’s ability to maintain even current living standards. So what could be done to promote innovation and technological advancement in South Africa?

First off, patent registration could be supported financially. It costs potentially hundreds of thousands of rands to get a good lawyer to advise on and register a patent, the more technically complex, the more expensive. That is not a flaw in our system, but a friction, nonetheless. The backyard innovator, studious engineer or workshop savant should not be kept from registering and monetising a patent just because of administrative cost.

Second, the government needs to reassess its fixation on policy interventionism generally, but particularly in mining. Or rather, administrative burdens and regulatory requirements need to be reduced. The chance of this happening is unfortunately low at best, but from experience, a large and organised push from industry for even small reforms often pays off.

Dr Steenkamp is CEO of Codera Analytics and a research fellow with the economics department at Stellenbosch University. Hanekom, Pretorius and Roos are Associates with Codera.