One test of the ‘strictness’ of an inflation targeting central bank’s stance is alignment between its inflation forecasts (or market expectations) and the bank’s target. The weight the central bank places on stabilising output also affects the speed of the adjustment towards the target. As a result, whether the Bank’s policy is consistent with elimination of capacity pressures (e.g. the output gap) and/or the consistency between its inflation forecast and the target can be used to judge the strictness of the bank as an inflation targeter.

A recent SARB working paper considers the historical consistency of SARB rate settings with output gap elimination and inflation target achievement, respectively. The authors suggests that the preferences of the SARB MPC have been for a stricter stance than that of a flexible inflation targeter since the adoption of their forecasting model QPM in 2017 (and a preference for a 4.5% midpoint target). They find that the MPC placed higher weight on the achievement of the inflation target than on closing the output gap.

It is a pity that the paper does not investigate the aspects of the underlying views of the MPC members and the forecasting staff that have contributed to historical policy rate settings. It would have been nice, for example, if the paper analysed historical differences between the forecasted policy rate and actual policy decisions to help draw out lessons from the Bank’s forecast errors. There has also been a lot of uncertainty recently about the MPC’s reaction function (i.e. how the Bank will react to specific economic shocks), reflected in persistent deviations in market expectations of interest rates and the policy rate projections. Yet the paper does not question whether changing the inertia in the policy rule (i.e., how quickly policy responds to deviations in inflation from the target) used in their modelling would have helped improve the achievement of the inflation target. Nor does the paper present a decomposition of historical policy rate levels into contributions from its assumed drivers (including the policy rule calibration, underlying trends and their estimated unobservables (such as neutral interest rates), for example). This type of analysis would help the Bank understand whether its policy rule in QPM is consistent with the revealed preferences of the MPC about the trade-offs between inflation and capacity pressures. It might also help to explain differences between MPC decisions, QPM projections and market pricing.

But tinkering with the policy rule is likely not sufficient to explain the differences between market pricing and actual monetary policy settings if these reflect differences in narratives about the outlook for the economy or an inconsistency between the calibration of the model and the market’s beliefs about the MPC’s preferences. Recalibrating QPM to reflect changes in the structure of the economy and transmission mechanism (which the authors do recommend in their conclusion) may also account for some of the differences between market pricing of interest rates, QPM projections and MPC policy settings.

The SARB stands out among major central banks for not communicating the economic narrative underlying monetary policy decisions through the lens of its main forecasting model. This confuses commentators and analysts to no end about what drives its policy decisions.

Let us use the recent larger-than-expected policy rate changes as an example. The SARB cut interest rates aggressively at the onset of the pandemic to deliver faster economic stimulus than QPM would have recommended. The SARB has also recently withdrawn that stimulus faster than QPM recommended. Whether the front-loading of cuts during the outbreak of the pandemic and the recent front-loading of hikes has been appropriate depends on whether the shocks that the SARB assumed were driving deviations in inflation from the target were part of a reasonable economic narrative. Encoding the QPM with the actual economic narrative of the MPC can help to identify the underlying reasons for a disconnect between the SARB staff forecasts and the MPC, as well as difference between the SARB forecasts and market expectations.

With the onset of the COVID pandemic, the SARB assumed that the pandemic and economic lockdowns would have predominantly demand-side impacts on the economy. Demand-side effects include a decline in consumption from reduced income, travel restrictions and increased uncertainty about the future. Demand shocks are assumed to cause a price adjustment that will equalise demand and supply, with quantities and prices moving in the same direction. A supply shock, on the other hand, would tend to see quantities and prices move in opposite directions. While a negative supply shock puts upward pressure on prices, a negative demand shock exerts downward pressure. Since supply shocks can affect output over the short term, a central bank’s take on their contribution to growth outcomes has implications for the estimation of the output gap, which proxies the extent of economic slack. The SARB’s initial interpretation of the COVID-pandemic’s impact on the economy implied that it created a massive output gap and that a lower policy rate would be consistent with meeting the inflation target. The possibility that the pandemic could also prevent the economy from returning to its pre-pandemic equilibrium could also have been part of the basis to advocate for an early and aggressive expansionary policy response to the pandemic.

The Philips curve framework SARB uses to think about the transmission of economic slack to inflation is based on the notion that slack is driven predominantly by demand shocks. So the SARB’s assessment of the relative balance of supply and demand shocks from the economic lockdowns had important implications for the appropriate stance for policy. By assuming the COVID pandemic was predominantly a demand shock, the SARB assumed a lot more policy accommodation was necessary than its policy rule would otherwise imply. This also meant that the recent spike in global inflation caught SARB (as it did some other central banks) by surprise, as they have been slow to revise their judgements about the underlying trends in the economy, for a long time holding on to a view that inflation pressures would be transitory despite growing evidence to the contrary.

Transparency about the parameterisation of models and the assumptions underlying projections help to explain the drivers of any differences between MPC decisions and official projections. This also helps to focus discussion about MPC decisions on the reasonableness of these choices.

It is therefore curious that the QPM framework has not been used to assess whether front-loading cuts beyond what the policy rule dictated helped to stabilise the economy. The appropriateness of front-loading depends on the reasonableness of MPC assumptions about future inflation expectations and the shocks that have driven output and inflation from their trend levels. This is exactly what a macroeconomic model like QPM is useful for and how reviews of monetary policy settings can help policymakers learn from their mistakes.

As documented in Monetary Policy Reviews and MPC statements, the SARB, like other central banks, eventually attributed more of the 2020Q2 fall in GDP to supply shocks. This gradual change in interpretation of economic developments amounted to an acknowledgment that the inflation impulse being observed was not just a temporary phenomenon and that risks to trend inflation were intensifying (see chart below).

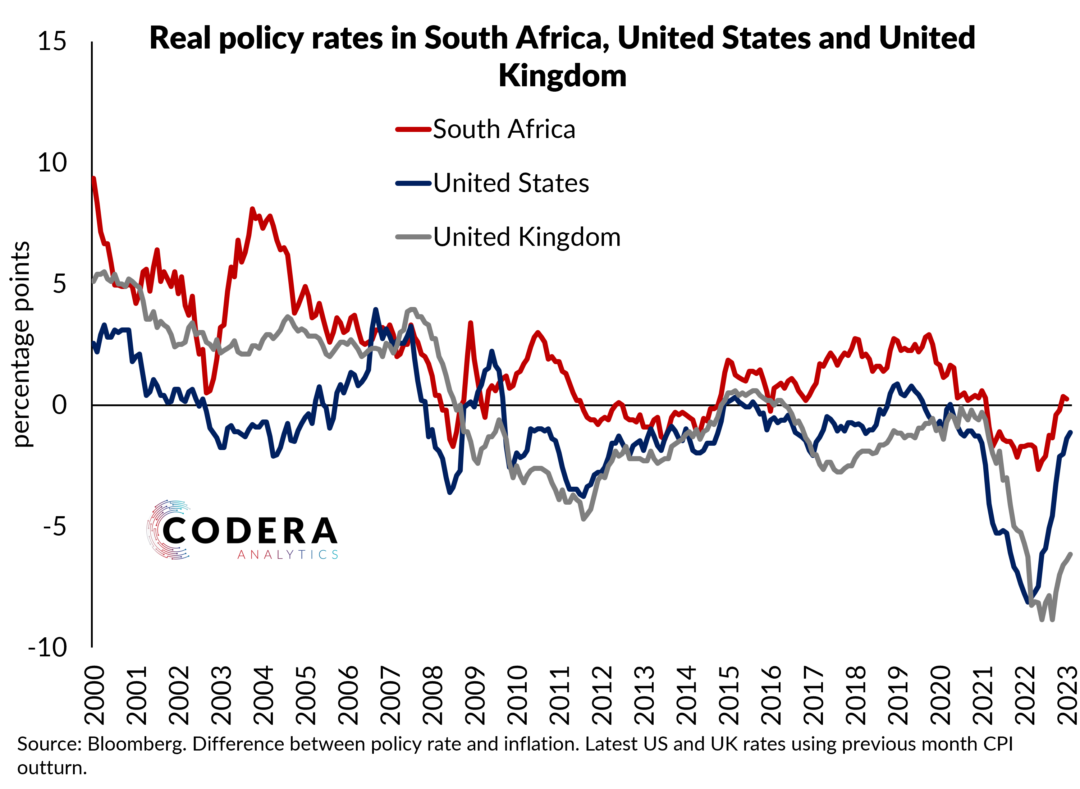

It is also highly likely that the COVID shock and ongoing electricity constraints are affecting macroeconomic relationships and trends in South Africa. This implies substantial uncertainty around estimates of potential growth, neutral interest rates or South Africa’s equilibrium exchange rate, all of which have important implications for assessments of the appropriate stance of policy. Between late 2021 and early 2022, markets began pricing in higher neutral rates and future short-term rates than SARB and other central banks have projected would be needed, and so there was a lively debate about whether SARB and some major central banks were `falling behind the curve’. Now the question is when major central banks will stop tightening.

It is therefore surprising that the narrative of the MPC members is not communicated through the lens of the QPM and that historical evaluations of policy decisions do not consider the reasonableness of the MPC’s business cycle narrative.