Today’s blog post is an ungated version of a Business Day article in which we provide extensive links to supporting evidence and estimates.

Understanding South Africa’s investment freeze

Despite the abundance of grand economic strategies and much publicised government-corporate “investment accords”, productive investment in South Africa has been slowing to a halt. South Africans are becoming poorer as a result. Our per capita income adjusted for inflation has been declining for a decade.

South Africa’s investment freeze reflects the impact of government intervention to make the economy more state-directed and orientated to achieving transformation goals. The government’s antagonistic stance towards business and its unwillingness to make hard decisions to address the fiscal deterioration have made things worse. Regular policy shifts related to land reform, nationalisation, and mining also keeps unsettling investors. One cannot subordinate all policies to public interest goals like transformation, without compromising investment, and long-term economic growth.

The tragedy is that this has occurred against a backdrop of historically high prices of our major commodity exports. In the past, commodity booms have driven economic expansion. Yet South Africa’s mining volumes have declined significantly for gold, diamonds and copper, and been fairly stagnant for other categories such as coal, iron ore and platinum group metals.

Why could South Africa not take advantage of this once in a lifetime opportunity? While loadshedding played a role, the deeper cause of the mining industry’s malaise is the same structural stagnation affecting the broader economy.

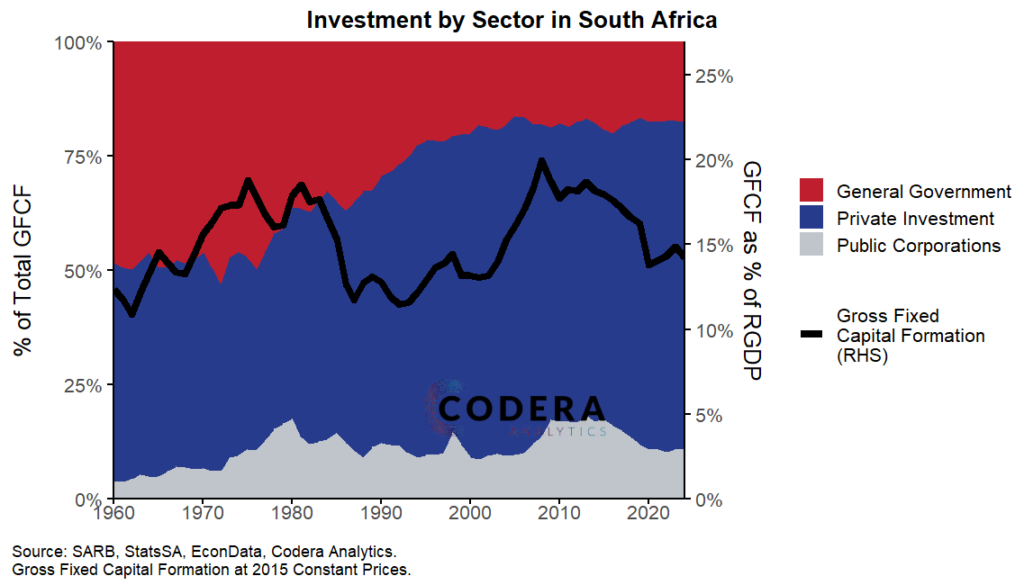

South Africa’s investment rate has fallen towards pre-democracy lows. The dramatic decline in government and state owned enterprise investment contributed significantly. But private investment makes up the largest share of investment and the private investment rate has been slowing over the last 15 years. Even venture capital investment is near multidecade lows.

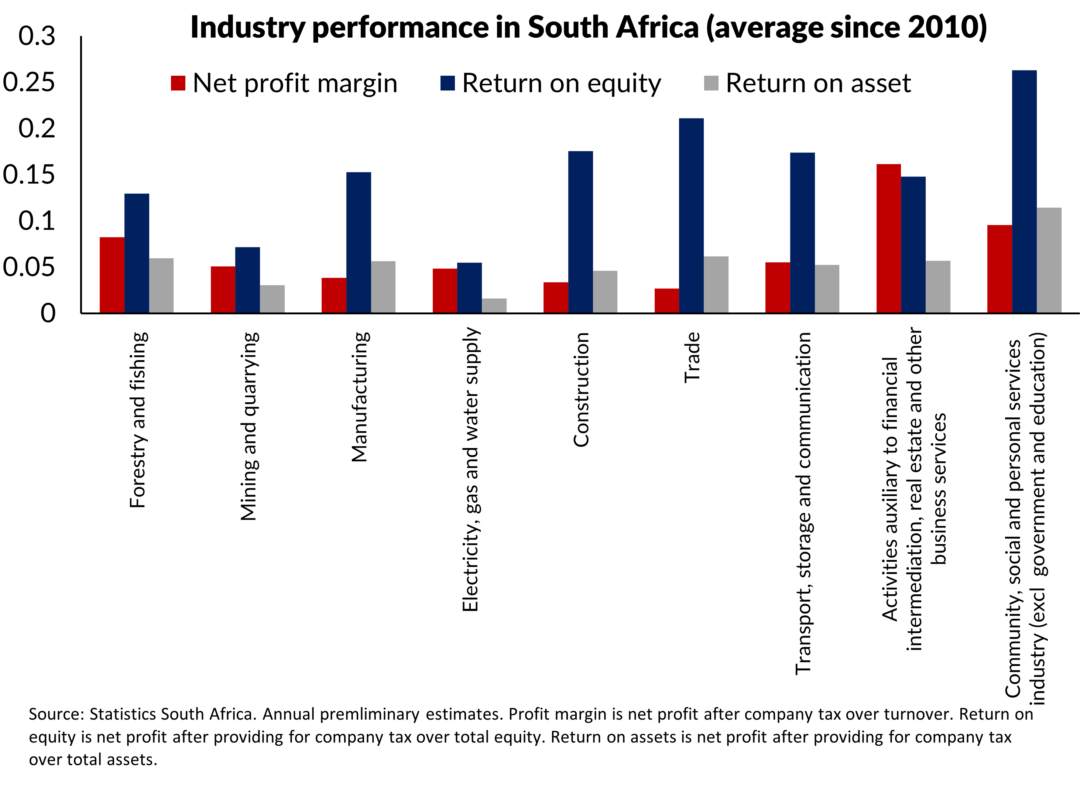

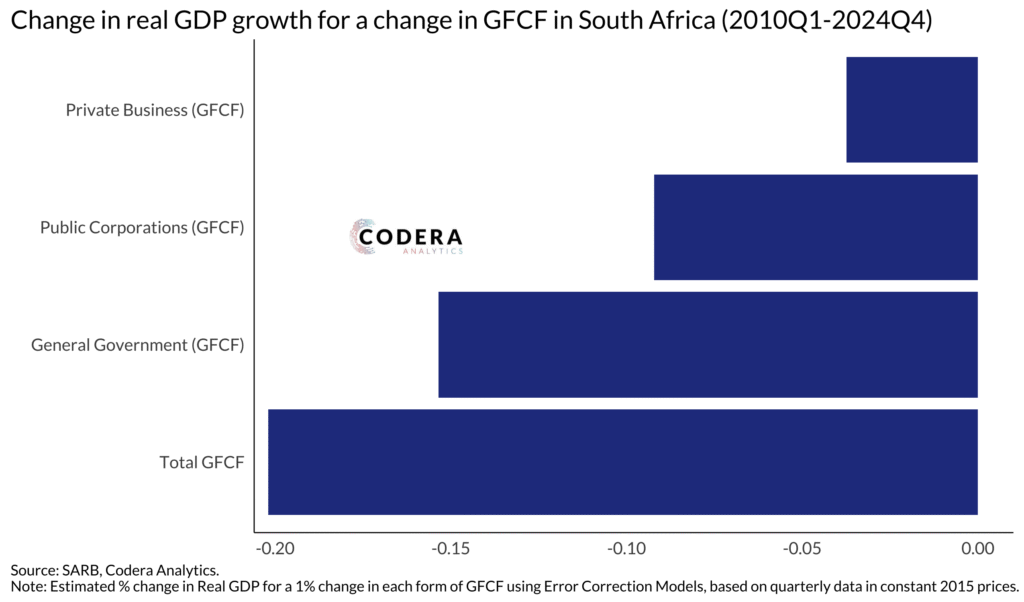

The economic return on investment has been declining. The return on inward foreign direct investment (FDI) into South Africa since 2000 has been around a third of what has been in Nigeria or Botswana. One can also see this in investment multipliers that provide a measure of how much GDP increases for every rand of investment. Before 2010, we estimate that the aggregate investment multiplier was larger than one-for-one. Since 2010, neither private nor public investment has stimulated faster economic growth. This reflects the decline in investment and economic growth over this period.

The result of a combined fall in investment and investment returns has been complete stagnation in productivity growth in over the last 15 years. Estimates from Productivity South Africa suggest that total factor productivity growth has flatlined since 2010. This means that South Africa’s per capita income will not increase over the long term – in plainer terms: the rest of the world will advance while South Africans will not.

This is evidenced by foreign investors avoiding South Africa. Reserve Bank data shows that foreign investors have withdrawn from local equities and bonds over the last several years, although it is hard to quantify accurately since dual listed shares distorts this picture. However, South Africa’s share of global FDI is down by around 75% since 2010.

Along with the decline in investment, South Africa’s depreciation rate has been rising. This means that the share of new investment going to replacing worn out capital has been rising. The consequence is that the capital stock of several industries in South Africa has declined since 2000.

This is a major problem as the capital stock is one of the major drivers of an economy’s potential growth. Estimates from the Conference Board show that capital deepening has historically been the most important contributor to South Africa’s GDP growth and that the contribution from the quality of the labour force and total factor productivity has been negligible.

The welfare implications of this slowdown have been massive. Had the economy continued to grow at its’ pre-2010 trend growth rate, real GDP per capita would have been more than 30% higher in just 15 years.

The outlook has also weakened dramatically as South Africa’s potential growth rate has collapsed. Our estimates are that potential growth remains below 1%, while the Reserve Banks has 1.1% for this year and still only 1.4% for next year. Estimates from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) are more pessimistic and suggest that South Africa’s per capita potential growth rate for 2020-2030 is negative 0.1%.

The government’s plan to arrest this decline involves doubling down on the policies that have been responsible for South Africa’s investment freeze and collapsing growth. The root cause of our economic stagnation is a philosophy of interventionism that assumes that economic growth requires redistribution, subsidies, and protection.

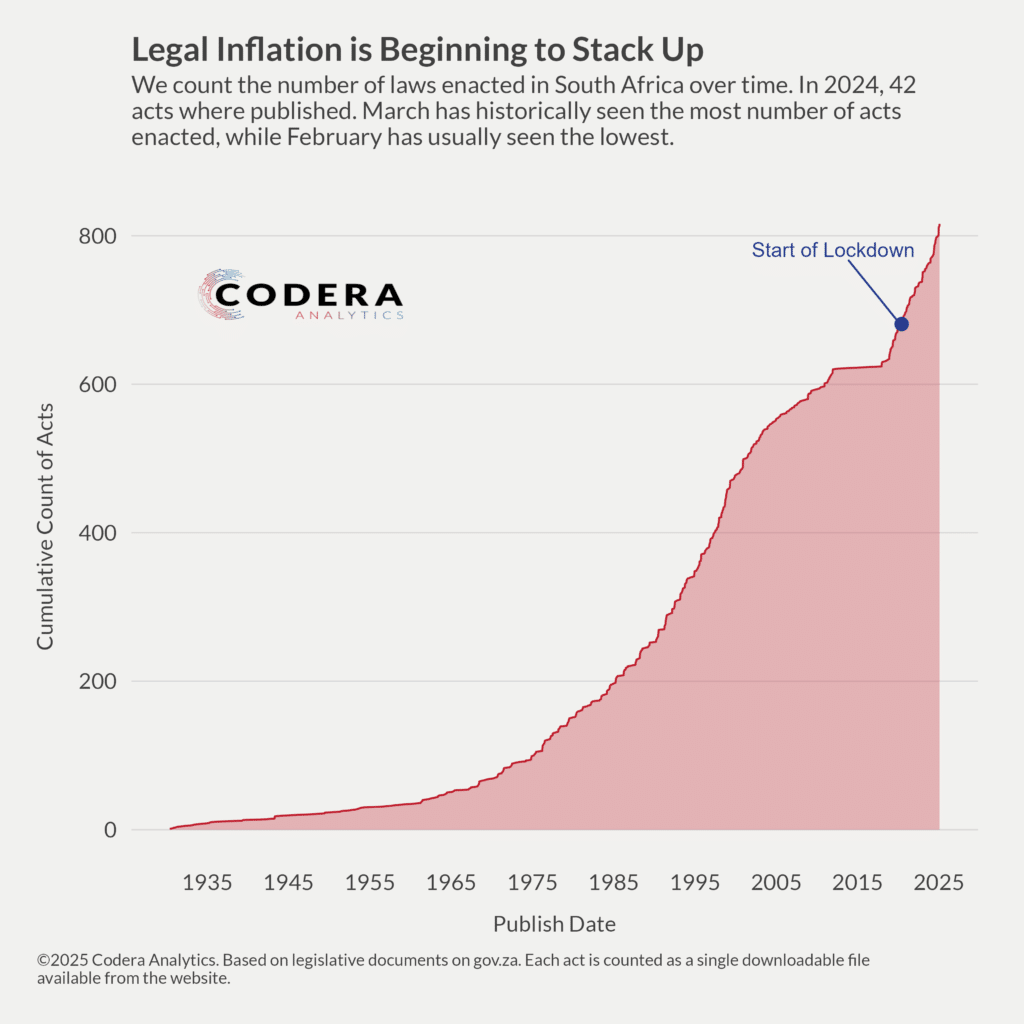

Government policy has become steadily more anti-growth. There has been a steep increase in the amount of legislation and regulations since 2010, increasing compliance burdens for businesses and citizens. The OECD’s assessments show South Africa has one of the most burdensome regulatory frameworks among major advanced and emerging market economies, restricting competition and FDI.

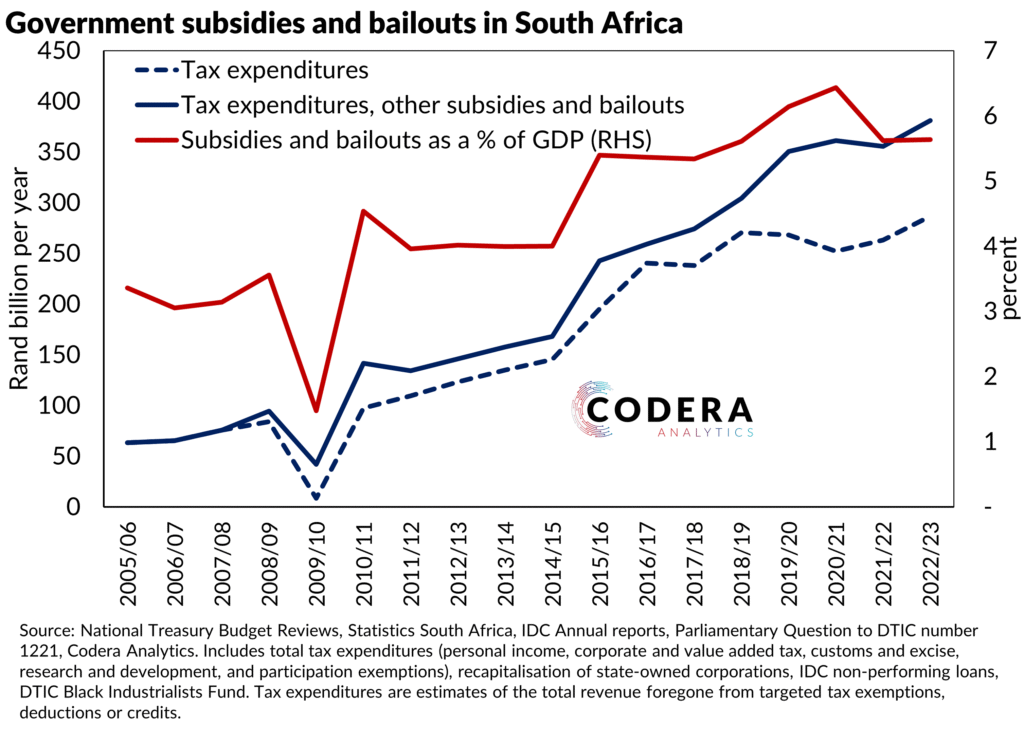

The size of the state and associated tax burden has grown dramatically, with the tax-to-GDP ratio up over a quarter to around 27% from 21% in 1994. Subsidies and transfer payments have risen to over 12% of GDP from 5% at the start of democracy. A larger proportion of public spending is also being directed at industrial subsidies and support for state owned enterprises. Between 2008/09 and 2022/23, explicit government subsidies and incentives totaled over R450 billion and recapitalisation of state owned corporations around R400 billion. South Africa has spent the equivalent of 10% of a year’s GDP bailing out zombie state owned enterprises.

These subsidies protect capital intensive, oligopolistic industries that do not create many jobs. And this support is becoming increasingly expensive. By its own numbers, Industrial Development Corporation co-investments cost over R1 million per job created. Tax exemptions cost the state about R350 000 per job of foregone tax for its support of the automotive industry. Corporate welfare and beneficiation policies have not only failed to create jobs, but beneficiaries have not become more competitive. In fact, our industrial sector has shifted to less sophisticated export products over time and South African manufacturing has become less integrated in global value chains.

The expansion of social grants has done a poor job of offsetting the impact of labour laws that discourage firms from employing people. It is scandalous that there is no forward momentum on labour market reforms that would make the economy more labour absorbing. Worse, the upcoming shift to quota-based employment equity regulations will further discourage firms from growing headcount and dramatically increase compliance costs. These regulatory settings are meant to be at Ministerial discretion and sector-specific, creating a lot of uncertainty and making long-term planning difficult.

Like industrial protection, a recent Harvard Growth Lab report highlights that black economic empowerment and government procurement policies aimed at transforming society have ended up creating a patronage network that resists any changes to the status quo. These regulations also raise the cost of government services. The IMF estimates that procurement policy reforms could save government as much as “20 percent of the cost of goods and services procured (3 percent of GDP)”.

Project Vulindlela-related reforms, while important, only address some of the symptoms of South Africa’s anti-growth disease. The underlying cause is increasing state interventionism, despite a collapse of state capacity. Reversing this requires a shift back to meritocratic appointments across all functions of government, privatization of failing state owned corporations, prosecution of the corrupt, and structural reforms that align South Africa’s policy frameworks to global best practice.

Dr Steenkamp is CEO of Codera Analytics and a research fellow with the economics department at Stellenbosch University.