In my article in Business Day, I argue that more oversight and accountability mechanisms would strengthen the foundation for the Reserve Bank’s mandate and public trust.

The South African Reserve Bank (SARB) is extraordinarily independent. Operational independence is a good thing in areas such as monetary policy, where it supports the achievement of low and stable inflation without political meddling. But SARB’s unelected officials wield powers that affect everyone in our society, so mechanisms that ensure democratic credibility are important for managing the tension between independence and accountability.

The SARB aligns with best practice in having its independence enshrined in the law, while providing disclosure via reporting to Parliament and publishing reports that explain its monetary policy and financial stability decisions. It also publishes financial and annual reports. But SARB stands out for its private ownership structure, its ability to set its own budget, a lack of clear procedures around governor appointments and dismissal, and limited oversight arrangements in some policy areas.

SARB is not unique in its budgetary autonomy or ownership structure, but these create symbolic challenges. Additional oversight and accountability mechanisms would strengthen the foundation for its mandate and public trust.

One area where greater transparency is needed is the determination of SARB’s budget and how it spends it. The SARB is funded through its seigniorage revenues from money creation and the reserve requirements it imposes on banks, as well as income from managing assets on behalf of government. One thing that is unusual about SARB is how little of the money that it produces is transferred back to government. The US Federal Reserve, one of the other remaining privately owned central banks, transfers profits amounting to almost 0.5% of GDP to the US government each year. The SARB did not transfer any income to the government between 2010 and 2019 and has not transferred any income since 2021.

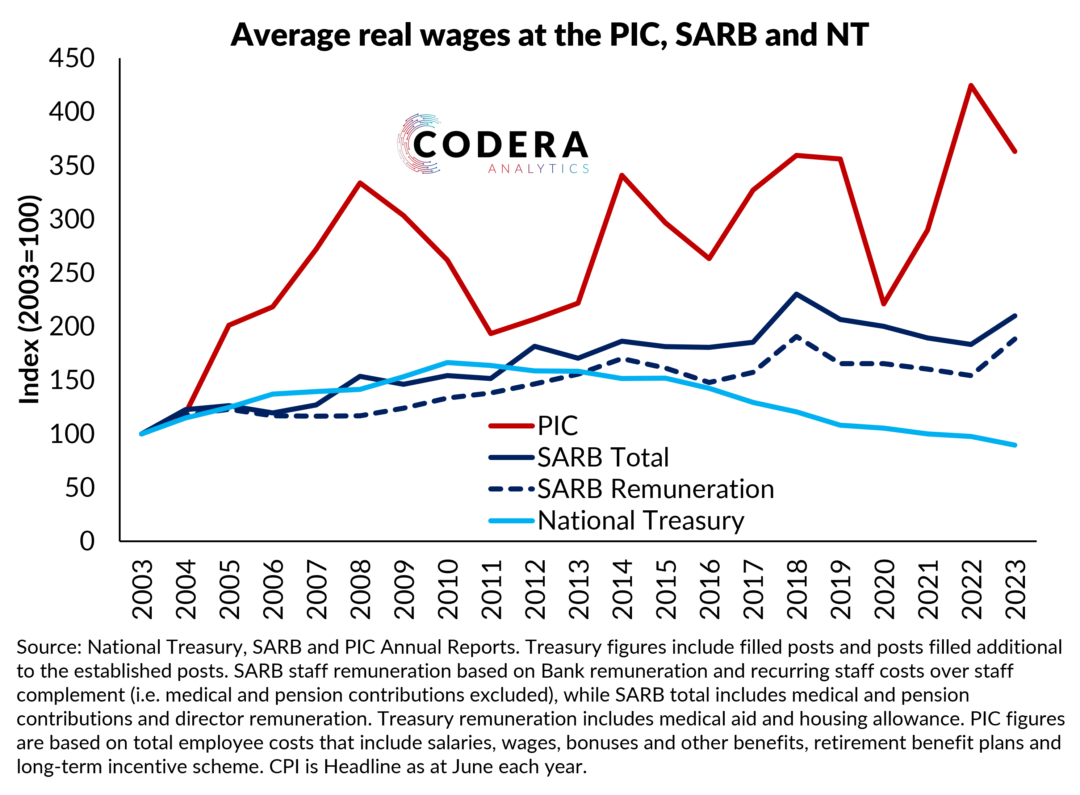

In most countries, the government also has some periodic say over the central bank’s budget. In South Africa, the government does not. The consequence has been that SARB has avoided the belt tightening that the rest of the public sector has been subject to since the global financial crisis. The SARB now stands out globally for how large its budget and staff costs are compared to the size of South Africa’s population and its budget, respectively.

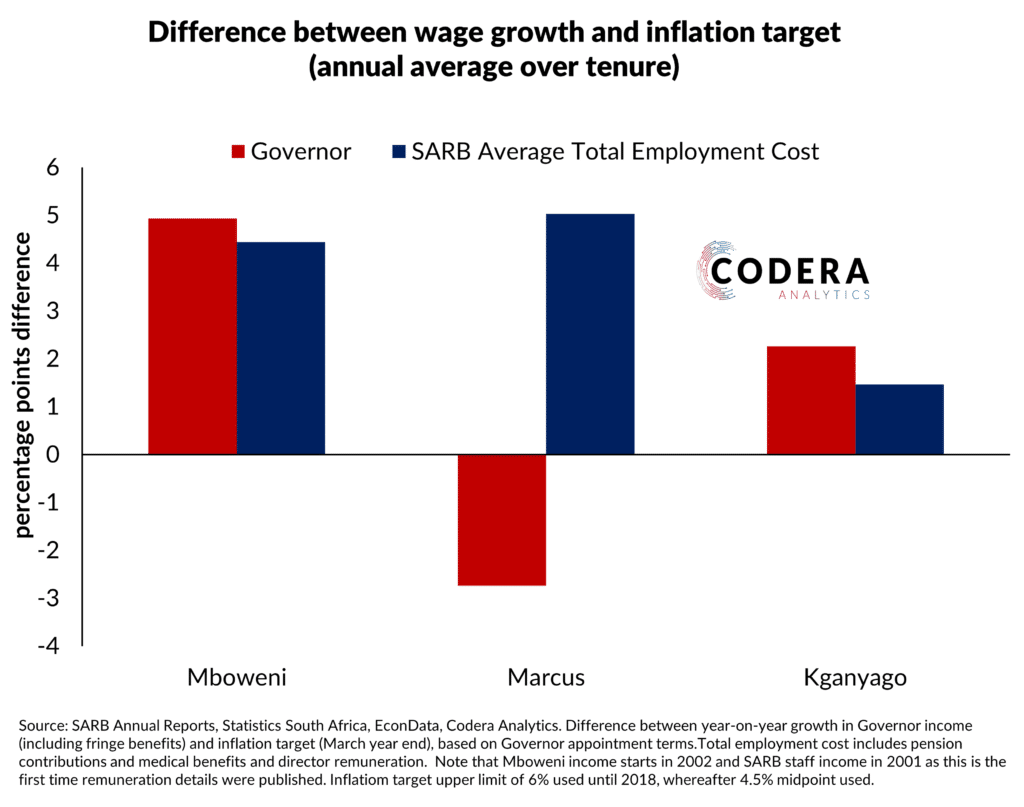

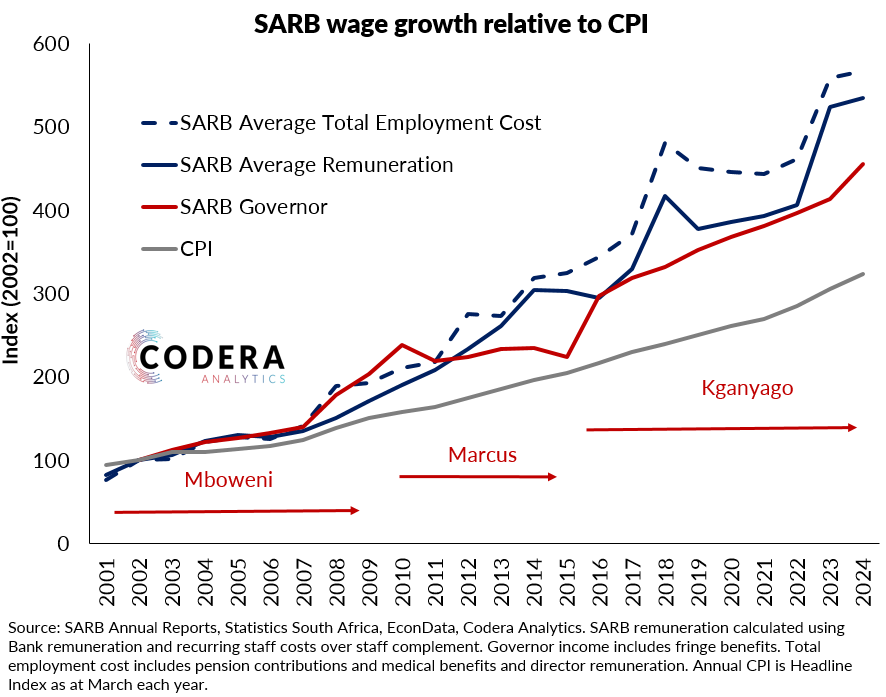

This raises questions around the institution’s commitment to its inflation target and means that it has more resources than the public institutions that provide oversight of it. Since 2002, SARB average wages grew at 8.3% per year (or 8.7% if benefits are included) while headline CPI inflation averaged around 5.5%. Most recently, Governor Kganyago received an annual increase of 10.2%. Fast wage growth has led to the average salary at SARB being almost double the latest available figures for averages salaries at National Treasury.

While SARB’s expenditure has been growing rapidly, its traditional seigniorage revenues have been under pressure. The ongoing decline in notes and coins in circulation means that since 2023 new currency issuance costs have exceeded the nominal value of new cash in circulation for the same year. This suggests that since 2023, SARB’s expenses consumed all of the seigniorage revenues from its monopoly on money production.

This means that the unremunerated reserve requirement has played a bigger role in sustaining SARB’s seigniorage revenues. SARB requires registered banks to keep 2.5% of their liabilities with it without receiving interest. We estimate that over the last year, the opportunity cost to banks has been about R12.5 billion (around 5 percent of banks’ average monthly net interest income). SARB does not publish seigniorage data, but we estimate that these have been approximately R80 billion (before production and distribution costs) since 2008. This is lower than the total implied revenues from unremunerated reserves, which we estimate have been around R100 billion. To put this into perspective: SARB’s annual income is more than government spends on provincial public transport.

Given the recent shift to a surplus-based monetary policy implementation framework, unremunerated reserves are no longer required to create a liquidity shortage in the banking system for the SARB to ensure influence over interest rates. The decline in its cash seigniorage is one reason the SARB may be reluctant to remove unremunerated reserve requirements, even if they are no longer required under the new policy implementation framework.

As we saw happen last year, SARB’s Gold and Foreign Exchange Contingency Reserve Account (GFECRA) account creates political pressure for unrealised foreign exchange profits to be monetised and used for other government purposes.

Reforming SARB’s foreign reserve management policy is long overdue, given the nation’s deteriorating sovereign financial position. We estimate that the SARB’s current approach is equivalent to a 0.5% of GDP annual insurance policy for SA Incorporated. Evaluating whether this offers value for money or not and whether SARB is doing a good job stewarding South Africa’s reserve portfolio is impossible given the limited information SARB publishes about its balance sheet management activities.

There are other areas where greater transparency would strengthen public accountability. Take the Prudential Authority as an example. It collects but does not publish institution-level regulatory compliance data, constraining market discipline of non-compliant institutions. Reviews that include substantive stakeholder engagement of South Africa’s financial surveillance and exchange control regulations are also past due.

Transparency and governance frameworks are crucial for ensuring that unelected technocrats are held accountable. The Phala Phala saga raised questions not only about political entanglement of SARB but also the consistency of its policy enforcement. Likewise, the recent high court ruling that SARB abused its exchange control powers in its treatment of Ibex/Steinhoff raises alarm about overreach by SARB and highlights the need for reform of exchange control and financial surveillance regulations and operational procedures.

SARB governance relies on oversight by a Board of Directors that includes seven appointed by the President and four elected by SARB’s private shareholders. The public biographies of several of the current directors do not show substantial technical expertise in the core policy focus areas of the central bank. Unlike the Boards of several leading central banks, the SARB Board does not publish oversight reports evaluating policy effectiveness and compliance in any detail.

SARB also stands out for having an executive-led governor appointment process. The governor and deputies are appointed by the President in consultation with the minister of finance, but the criteria for appointments are not public, nor are dismissal protections clearly defined.

The adoption of inflation targeting in South Africa with a committee-decision making process and disclosure of forecasts and judgements reflects an appreciation that public confidence depends on transparency and governance arrangements. Given the extraordinary power wielded by SARB’s governors, governance arrangements are crucial to protect the public against the possibility of poor decisions from inexperienced or rogue governors in future.

Reform to the appointment process to be more transparent, regular oversight reports and external reviews of funding, policy implementation and framework compliance would strengthen public confidence that the Bank is discharging its responsibilities competently and advancing policy in the broader interest of South African society.

Many have worried that legislative reform of the SARB’s private ownership structure and governance arrangements could see the institution’s mandate also being revised. The existence of the Government of National Unity mitigates these risks somewhat. It also creates the opportunity to align SARB’s governance and accountability arrangements more fully with leading inflation targeters.

Dr Steenkamp is CEO of Codera Analytics and a research fellow with the economics department at Stellenbosch University.