In today’s blog post, I repost my Business Day article in which I argue that SARB is not behind the curve as some have suggested, though it might not have as much space to cut as it currently projects.

Is the Reserve Bank behind the curve?

Prominent journalists and commentators are asking the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) whether it thinks it is ‘behind the curve’. But which curve, and by what measure could it have fallen behind?

Usually, the focus is whether the policy rate is keeping pace with inflation. Sinc Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation has been slowing, the question is whether the SARB should be easing policy faster. Our view is that, based on four key considerations, the SARB has not fallen behind the curve, but rates may not have as far to fall as many people hope.

Over recent months, the gap between the policy rate and core inflation has been rising, suggesting that there may be scope to loosen policy. Measures of underlying inflation highlight the influence of volatile components on overall inflation. Now that headline inflation (4.4% in August) and core inflation (4.1%) are close together it suggests that pressures from unstable price categories such as fuel prices have dissipated.

The share of detailed CPI components growing above the mid-point inflation target of 4.5% has also fallen below 50%. This marks a significant development in the inflation landscape, signalling that inflation pressures may be easing across a range of goods and services.

However, there are lots of different ways to measure underlying inflation so there is always uncertainty around these judgements. Our core inflation measure, CPI-Common, a model-based measure of common price changes across categories in the CPI basket, suggests that there remains more broad-based inflation pressure than implied by the Statistics SA core measure.

Some would argue that the SARB merely follows the US Federal Reserve (Fed). Every time the Fed changes its policy rate there is speculation about whether the SARB will follow suit. Since 2000, the correlation between the 3-month lagged fed funds rate and the repo rate is only around 0.5, suggesting the SARB has not tended to directly follow US monetary policy. The coincidence between US and SA monetary policy has varied a lot over time, with South African events like Nene-gate and the 2016 drought contributing to periodic divergences.

Whether the SARB follows the Fed ultimately depends on how correlated South Africa’s economic cycle and capacity pressures are with those of the US and the extent to which relative interest rates and currency movements synchronize underlying inflation pressure. It is also worth noting that the Fed’s mandate includes supporting maximum employment, which makes US monetary policy more reactive to US labour market developments. In the US, demand pressures have been softening, although nowcasts suggest there remains a lot of built-up capacity pressures.

A second consideration is the output gap, or slack, in the economy. SARB estimates that the output gap remains slightly negative here, suggesting a lack of capacity pressures. SARB’s negative output gap projections also implies that it thinks there is space for policy cuts over the next couple of meetings. But since GDP data get revised and one cannot observe economic slack directly, this is another area of uncertainty. Our statistical analysis, which in recent years have been more aligned with the IMF than the SARB’s estimates, suggest there is less slack at present. This would suggest that cutting rates too far could see inflation pressures re-emerge.

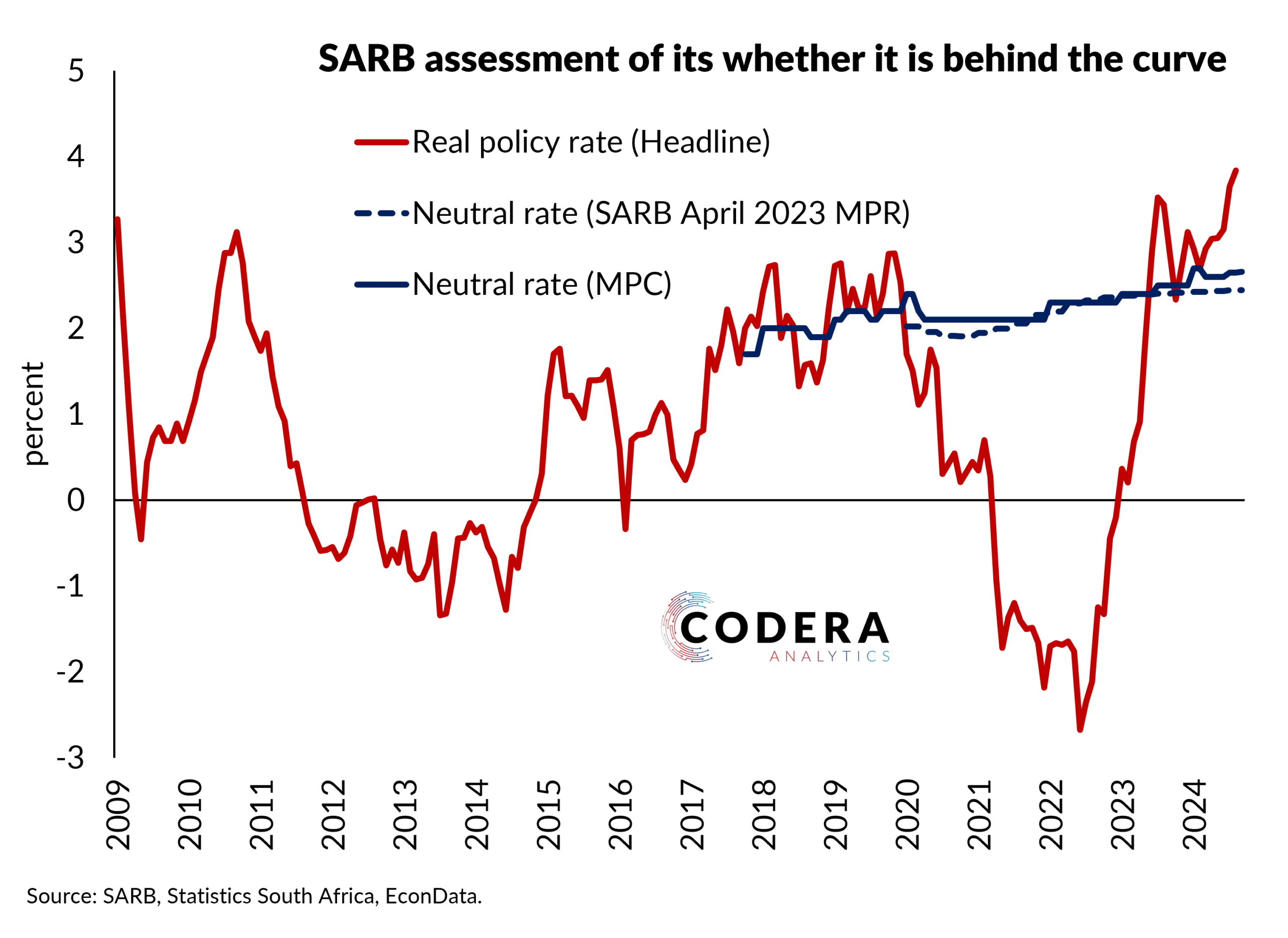

A useful concept for assessing the stance of monetary policy is the neutral interest rate. This is an estimate of the level of interest rates consistent with inflation at the target and output at its full potential. SARB has revised its neutral estimate upwards over recent months and currently estimates a terminal neutral rate of around 7%. This implies that the SARB thinks that the policy rate is currently restrictive and gradual policy easing would be consistent with achievement of the inflation target. Their current estimate suggests another 100 basis points of cuts would be consistently with shifting to a neutral policy stance over the medium-term. Again, because we cannot observe the neutral rate, economists will argue over whether SARB’s assessment is correct.

A third consideration is financial markets. Financial markets embed expectations of interest rates and inflation and so one can also use market pricing to assess the market’s assessment of whether the central bank’s policy is keeping up with changes in economic conditions or falling behind. One can assess whether policy decisions are in line with market expectations, and use models to measure long term interest rate expectations. We estimate that market pricing implies a slightly higher terminal neutral rate than SARB’s estimate.

A fourth consideration is whether inflation expectations of consumers and businesses are moving towards the inflation target. Inflation expectations have remained stubbornly above the inflation target, although they have been falling over recent quarters. Again, inflation expectations may not be measured without bias, so economists tend to argue over whether monetary policy should do more to anchor inflation expectations at the inflation target.

Any assessment of the appropriateness of the SARB’s stance requires evaluating of the state of the economy, financial conditions, asset markets, and consumer and business expectations. Economists often make strong assertions about the future, but evaluations of economic conditions and the outlook involve a lot of uncertainty.

What really matters is applying a consistent framework to interpret how economic and financial developments will affect how the central bank will react. It is not enough to just look at what other central banks are doing as South Africa’s economic cycle has not been strongly aligned with global dynamics.

Whether SARB is behind the curve depends on the credibility of the Bank’s assumptions and economic narrative about the future. In our assessment, the SARB is not currently behind the curve, but it might not have as much space to cut as it currently projects.

Dr Steenkamp is CEO of Codera Analytics and a research fellow with the Economics Department at Stellenbosch University.

Footnote

MPC neutral estimates in the charts are based on the current year neutral rate estimates from each MPC meeting.