The SARB publishes a Monetary Policy Review (MPR) twice a year, offering insights into its assessment of the economic outlook and the appropriate monetary policy stance. Key takeaways from the latest MPR included:

- That the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) views risks to the outlook for inflation as broadly balanced

- Inflation expectation anchoring has declined relative to the pre-pandemic period, consistent with our analysis that SARB stands out globally for having more work to do to fully anchor expectations

- The SARB expects growth of 1.1% in 2024 (potential at 1.3%) and 1.6% next year (1.4% next year, higher than our statistical filters suggest)

- SARB estimates that the introduction of the two-pot retirement system would create a small economic stimulus over the next two years of 0.1% in 2024 and 0.3% in 2025.

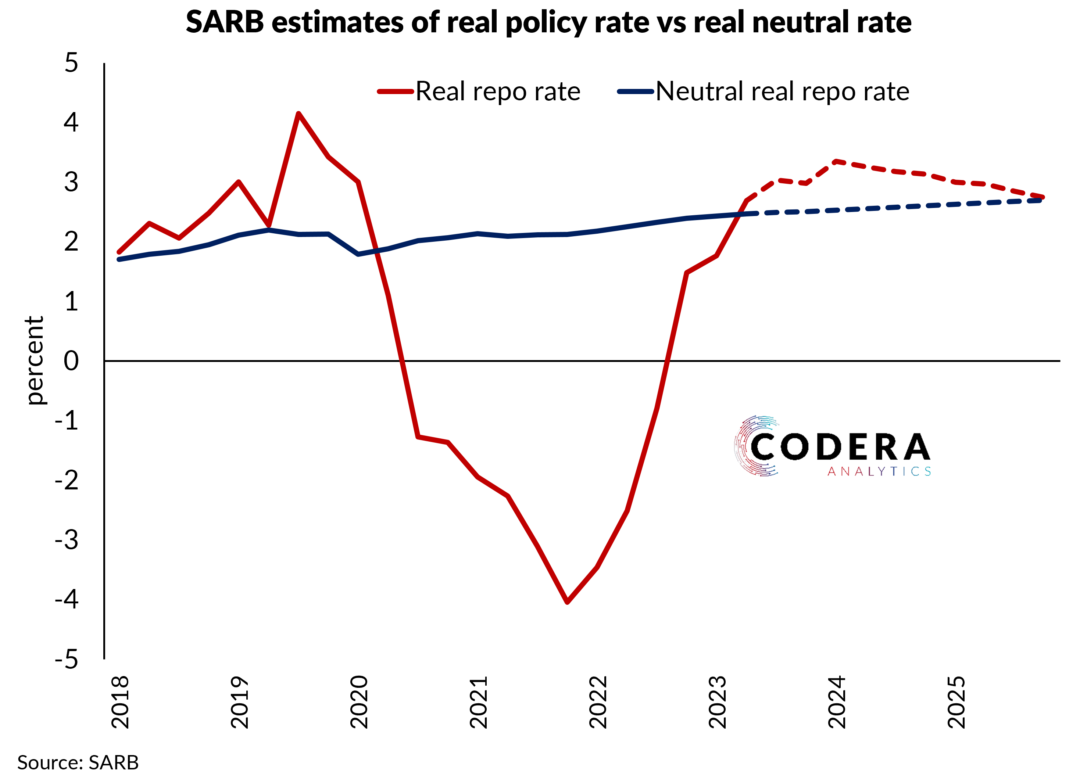

The highlight was that SARB is finally communicating the implications of risks to the projections for its policy stance by providing forecast scenarios. This helps the market understand the MPC’s policy preferences more fully, promoting a risk management approach to monetary policy. It would be great to see this more regularly for other assumptions about the outlook. The scenarios show that their baseline projections imply a further 100 basis points of cuts should inflation fall in line with its projections. If inflation falls by more, then there is room for more cuts, or less cuts if inflation does not fall as far as expected.

It was notable that the MPR did not mention the possibility of a revision to the inflation target. Given how often the issue is discussed in macroeconomic policy discussions, it remains surprising how little analytical work has been released on the topic in South Africa. If the SARB intends to lower the target, it is likely that it would need to keep rates higher than it currently projects.

It was also good to see the SARB revise its interpretation of the economic impact of the COVID pandemic, communicating that it now assumes that the pandemic was predominantly (75%) a supply-related shock, after assuming the opposite in the immediate wake of the pandemic. This matters because the SARB previously assumed that there would be downward pressure on inflation from the fall in growth, leading it to under-appreciate the risk of upward inflation pressures and a lower policy rate path than had it assumed a larger role for supply in driving inflation. This meant that the spike in global inflation in 2021 caught SARB (as it did some other central banks) by surprise. This revision also recognises that there is a risk that the recent decline in inflation outcomes may overstate the decline in underlying inflation suggested by core inflation.

It is notable that the potential impact of fiscal policy on monetary policy has not been assessed, especially considering the recent integration of a fiscal block into the SARB’s QPM model. The SARB did note that ‘the expected fiscal consolidations that are required to lower debt levels may reduce growth (and inflation) in the near term, lower inflation supports easier credit conditions, providing impetus to growth over the medium

term.’ But the outlook for fiscal policy, and its implications for growth, inflation, financial conditions and credit risk deserves quantitative analysis. For what its worth, here is our assessment of the cyclical impact of the government’s fiscal stance.

The MPR also noted that the implementation of the new Gold and

Foreign Exchange Contingency Reserve Account (GFECRA) framework and transfer of funds to National Treasury ‘resulted in the surplus liquidity level doubling to R160 billion over the review period. With market conditions improving generally, there were no distortions observed in price formation in money markets and in the funding behaviour of banks in the secured and unsecured interbank market.’ It would be nice to see formal analysis of the macroeconomic and financial market implications of settlement of GFECRA balances in future MPRs.