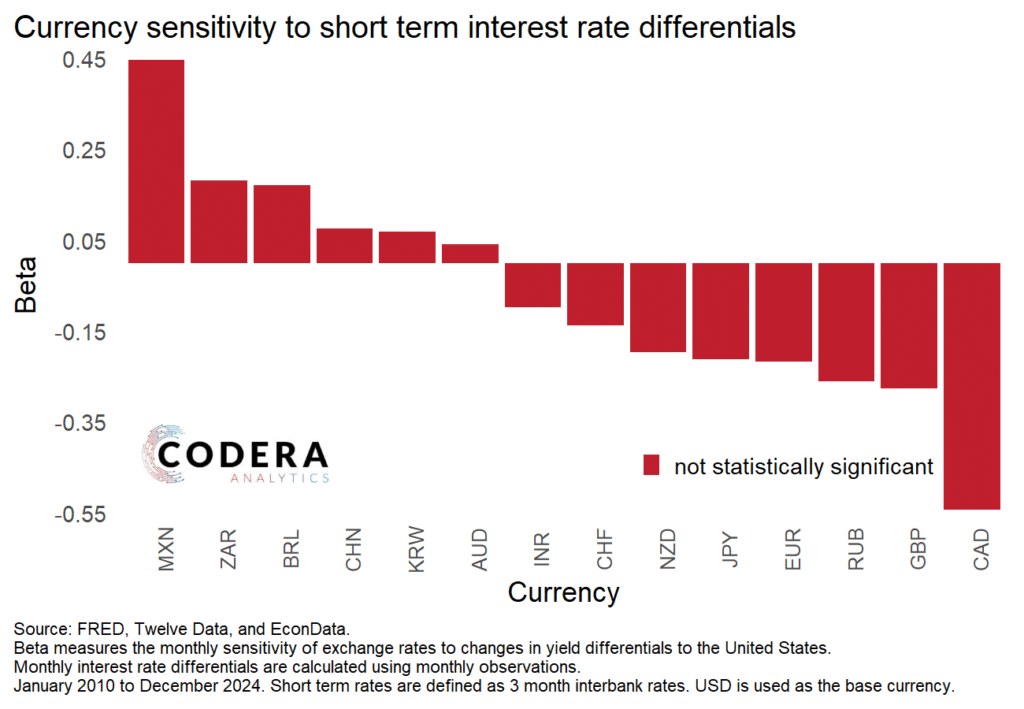

How sensitive are major currencies to interest rate differentials? Today’s post compares different currencies’ interest rate beta, defined by regressing changes in each currency (relative to the USD as the base currency) against shifts in interest rate differentials. Uncovered interest parity would suggest that an increase in interest rate spreads would be associated with appreciation of the quote currency (i.e. a negative beta in the charts below). However, many currencies display a positive beta at a monthly frequency – such as the Mexican peso, South African rand and Brazilian real. The Canadian dollar the highest negative beta, while other currencies display lower sensitivity to interest rate changes. None of the results are statistically significant, however.

These low, insignificant betas reflects the fact that currencies are affected by many other factors – things such as trade flows, market sentiment and country-specific shocks – during each month.

This is one reason why one should discount pronouncements by economists about the currency moving sustainably in a certain direction based on their prediction of a central bank policy decision. But this does not mean that interest rates do not matter for currencies. The chart below shows that these currencies have been more sensitive to changes in long-term interest rates differentials.

Currencies are the most flexible prices in the economy as they are immediately affected by shifts in financial markets. This means that, despite what economists on news programmes might claim, simple heuristics just do not explain their dynamics very well.

The chart below shows, for example, that one obtains very different beta estimates if one considers month-to-month changes in currencies and interest rates at a daily frequency instead of a monthly frequency as in the other two charts. This is because currency drivers, and their statistical relationship to the currency, are complex and time-varying. If one were to use a kitchen-sink model that considers a large number of potential explanatory factors of the rand and let the data determine how to weigh up different factors, one is able to explain movements in the rand using factors such as inflation differentials, sovereign risk and the value of the dollar. But the contribution of interest differentials alone is often not aligned with economic theories. So beware of economists bearing single variable (and single model!) forecasts.

Compiled by Oliver Guest

Footnote

We showed in an earlier post that the correlation between the policy spread with the US and the value of the rand has often run the other way, with the exchange rate depreciating during periods when rates have risen more in SA than in the US.

One also sometimes hears South African economists argue that the SARB’s MPC relies on high relative interest rates to keep the rand strong and inflation down, but we showed in this earlier post that the correlation between the policy spread and the value of the rand has often run the other way.