The South African Reserve Bank (SARB) publishes composite business cycle indicators to provide an early signal of what economic data imply for economic conditions. Analysts have been interpreting a pick-up in SARB’s leading indicator as a sign that economic growth will recover this year. But do these indicators help to predict GDP?

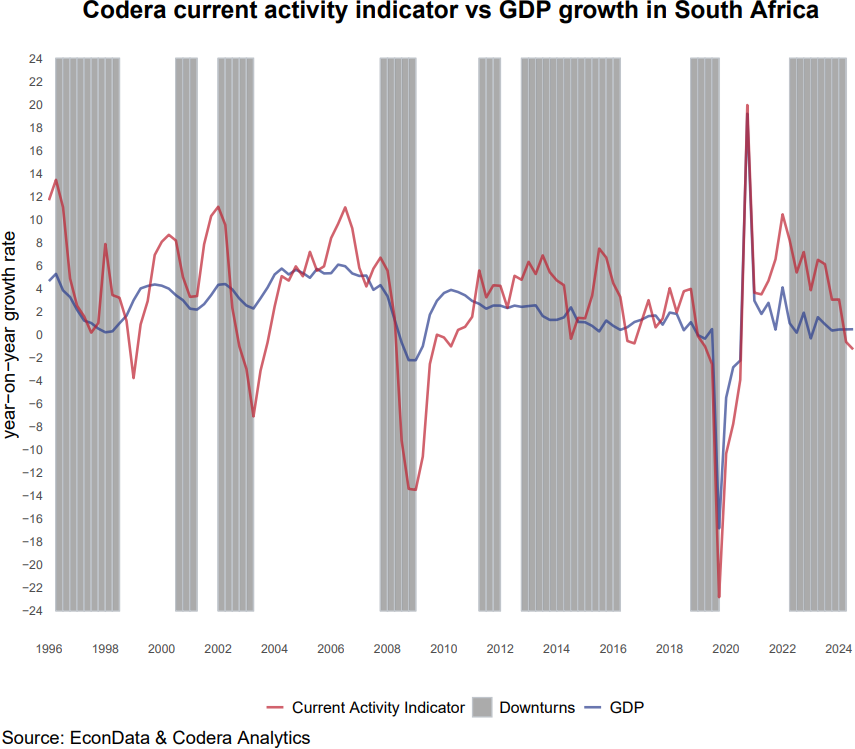

In today’s post, I investigate the usefulness of the coincident and leading indicator for forecasting GDP. To be useful, business cycle indicators need to provide more accurate forecasts that if we were just using the information from GDP alone to predict GDP. To test this, I estimate a rolling regression starting in 1980 and then produce an out-of-sample forecast of real GDP using either GDP itself, or the business cycle indicators. I find that neither the leading indicator or coincident indicator produce better forecasts than a simple AR(1) model (that just uses past values of GDP to project future values). At a one year ahead horizon, on the other hand, the coincident indicator produces slightly more accurate forecasts than the AR(1), but the leading indicator does not. As the second chart shows, this is because when the pandemic hit, the coincident indicator embedded information about the collapse of activity during March to April 2020. Prior to 2020, however, it performed worse than the AR1 model.

Since GDP data (and the business cycle indicators) get revised over time, it is important to evaluate whether the real-time performance (i.e. with data as currently available) of the indicators differs from their ex-post performance (i.e. once data have been finalised). Using EconData, I construct a dataset of real-time GDP data back to 2010, but unfortunately cannot easily do the same for the business cycle indicators. Ex-post business cycle indicators provide a slightly worse forecasts of real-time GDP, but the coincident indicator comes out marginally on top. Again, most of this reflects its superior performance as predictor since the pandemic. Even though this analysis does not use a full history of the real-time business cycle indicators, it raises questions about the usefulness of the leading indicator as a predictor of GDP.

Lastly, it is worth mentioning that another test of the usefulness of these indicators is whether they can correctly predict turning points in GDP. I will investigate this in a future post.

Footnotes

It is worth emphasizing that different regression specifications could be used to assess the usefulness of these indicators. Though one might obtain different results using different approaches, the approach used is a simple ‘sniff test’ of whether using these indicators to make unconditional statements about the outlook for GDP, as many market analysts do, is likely to be appropriate.

It would be great to redo this analysis with a a true real-time dataset. If anyone is interested in constructing a full true real-time dataset of South African macroeconomic data for forecast analysis, please contact me.

Our earlier paper on GDP nowcasting which was published in SAJE found in 2020, that the leading indicator was one of the 20 or so top predictors of GDP across different modelling frameworks, including machine learning models and vector autoregressions. The forecasts errors reveal that the coincident indicator was better at predicting GDP growth around the time of the COVID-19 pandemic than the leading indicator and so it is likely that this assessment may have change in the aftermath of that shock.

Lastly, it is worth emphasizing that not all leading indicators are equal and that the usefulness of leading indicators often changes over time. We showed in an earlier post that banking activity was strongly correlated with the Reserve Bank’s coincident indicator and GDP growth during the pandemic but since then, the correlation between BankServ’s BETI and same quarter GDP outcomes has weakened. I also intend to compare the ability of the indicators to predict turning points in GDP in a future post.