Today’s blog post provides a version of our Business Day article on the transition costs to a lower inflation target that includes extensive supporting links.

A team-SA approach needed for a low cost transition to a lower inflation target

In July the Reserve Bank monetary policy committee (MPC) surprised the market by announcing a 3% preferred inflation target. While a lower target is desirable, promising a lower target without co-ordination with the National Treasury and government as a whole could damage the Bank’s hard-won credibility.

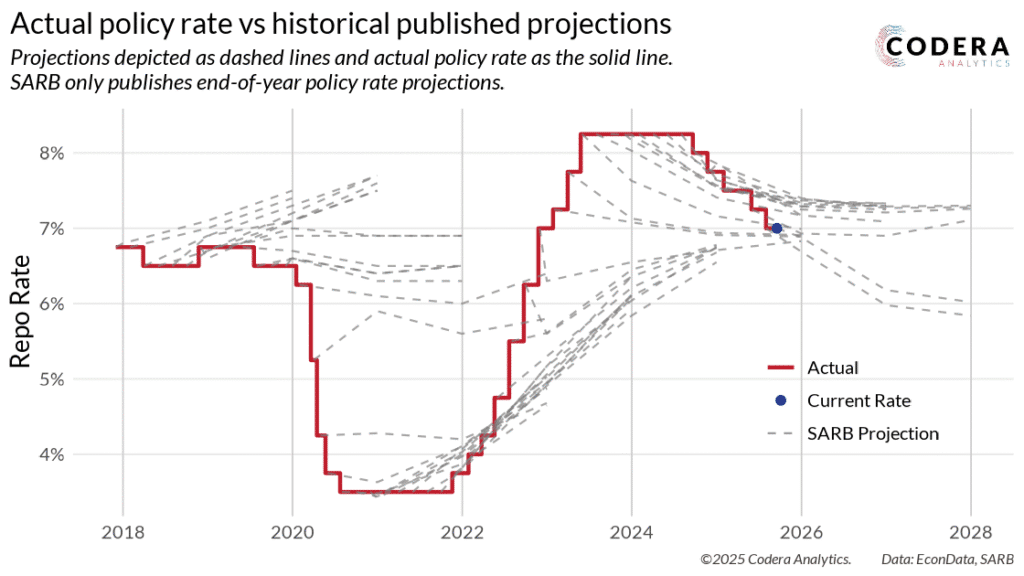

Bank projections imply that an inflation target of 3% instead of 4.5% would enable it to cut the policy rate over the short term, and keep rates 150 basis points lower over the long-term. Achievable with lower interest rates, this would mean a lower target would come at a very low economic cost.

Whether the Bank’s analysis is realistic hinges on whether its assumptions about how quickly inflation expectations will re-anchor to a lower target are realistic, whether fiscal policy will be supportive and whether the government buys into a lower target.

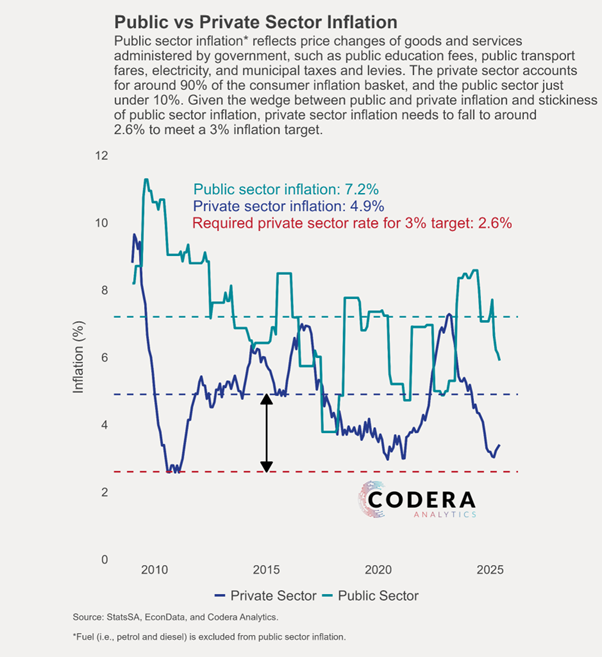

Without accompanying structural reforms, inflation in parts of the economy where prices are flexible (such as the tradable sector that is exposed to international competition) would also need to undershoot whatever a new target might be. Public sector inflation (things such as electricity and municipal rates) has averaged over 7% since 2009. Unless this is brought under control SARB will need to lower private sector inflation to unprecedented levels. We estimate private sector inflation would need to fall to around half of its average level since 2009 (just less than2.6%).

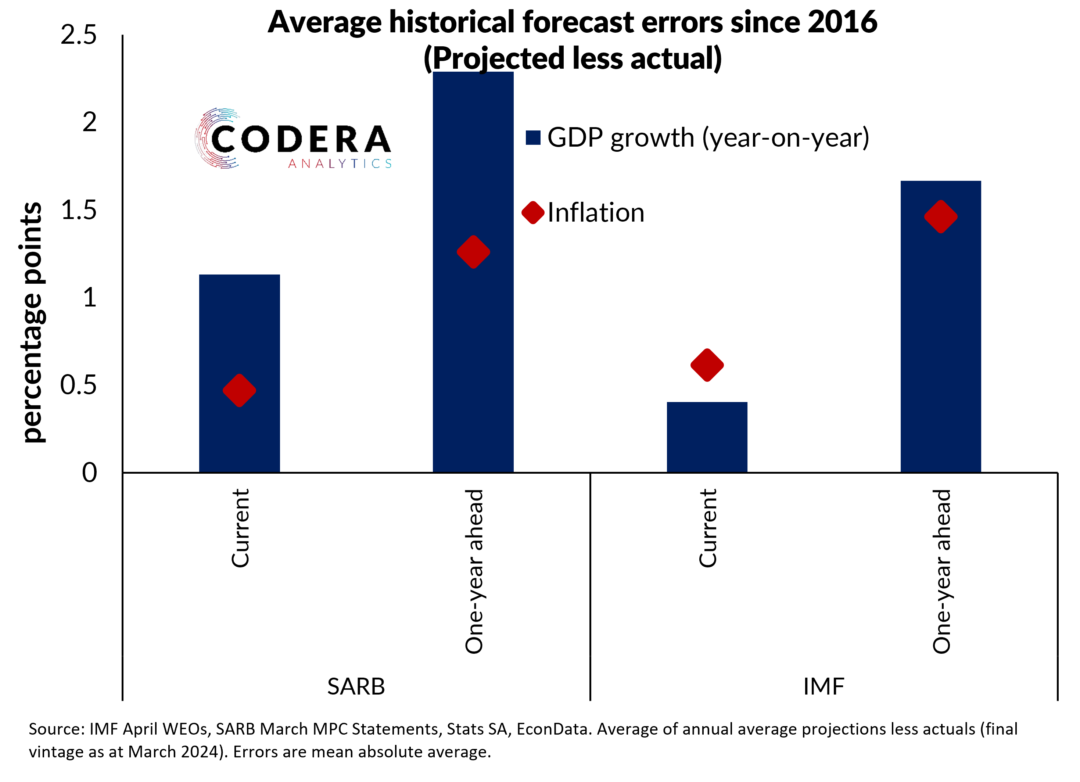

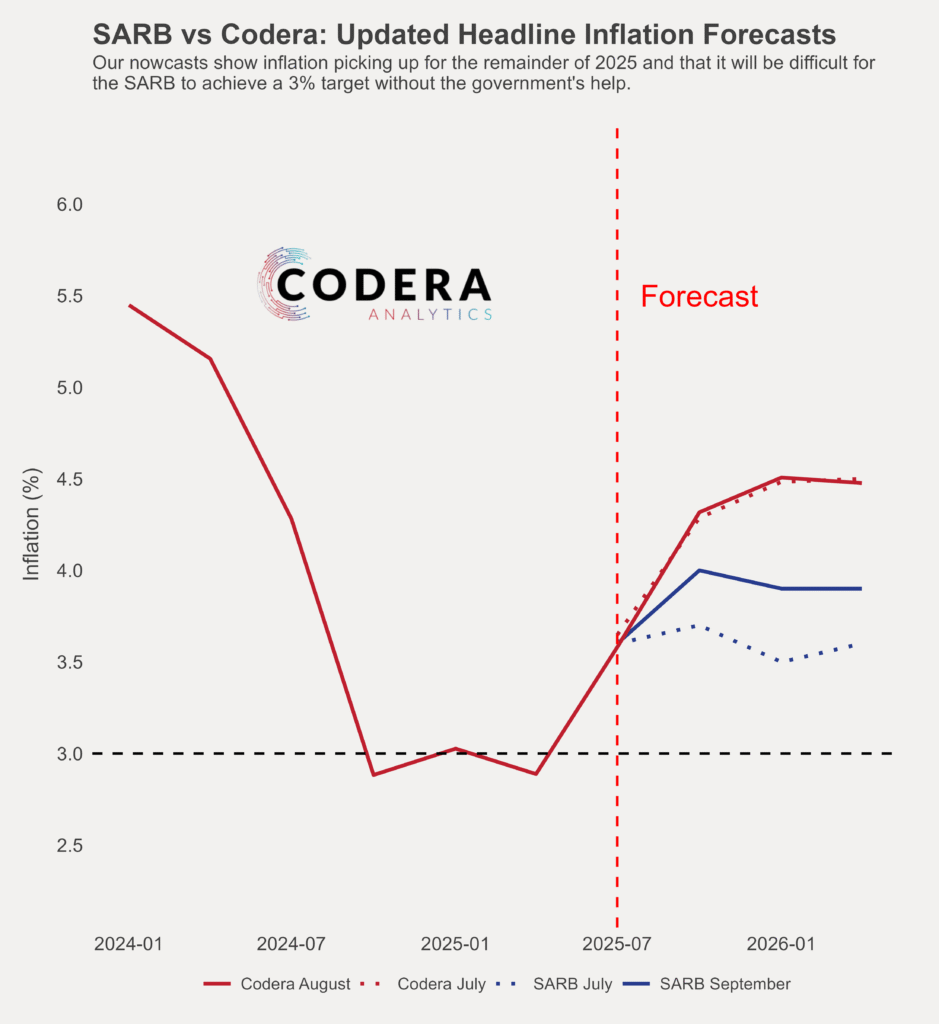

The Bank’s updated projections have inflation picking up to 4.1% by year end, before gradually declining under the assumption that inflation expectations fall towards 3% over time. Our projections have inflation heading towards 4.5% in December, as we forecast the exchange rate to weaken and food inflation to rise. Even the Bank expects it to take a long time for the new target to be entrenched: its latest projections only see the 3% target achieved in the fourth quarter of 2027.

The good news is that inflation expectations are continuing to decline. But, as we have shown in our research, inflation perceptions take a long time to adjust. When SARB announced a preference for 4.5% in 2017, it took around four years for inflation expectations to converge on the lower target.

The post-pandemic cost of living crisis of 2022-23 saw inflation expectations unanchor once again and only converge on the target again in late 2024 as the inflation cycle turned. The Bank will be unable to lower interest rates in the coming year unless its forecasts of decelerating inflation and its assumption about rapid reanchoring to a lower target bear out.

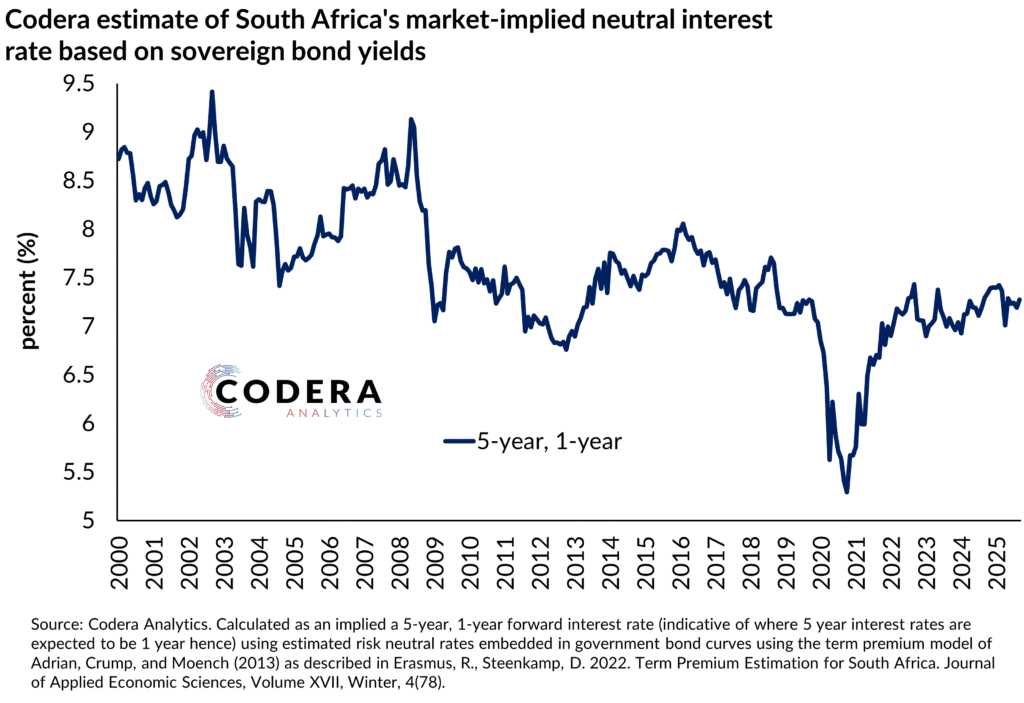

The Bank argues that a lower target implies that monetary policy has shifted to a mildly restrictive stance. Economists use a concept called the neutral rate to judge the effect of the level of the policy rate on the economy. The neutral rate is the rate that keeps the economy steady — neither stimulative nor restrictive — when inflation is under control.

The Bank’s neutral estimate is 2.8% for 2025 after adjusting for inflation (5.8% nominal assuming a 3% inflation target or slightly above 6% if inflation expectations are assumed to be partly backward-looking). This implies tight policy, as the 7% policy rate is above that level.

As neutral cannot be observed, economists will always argue about what its true value is. We estimate that the market-implied neutral rate is closer to 7%, so there is reason to question whether further cuts would be consistent with achieving a 3% target in the long term.

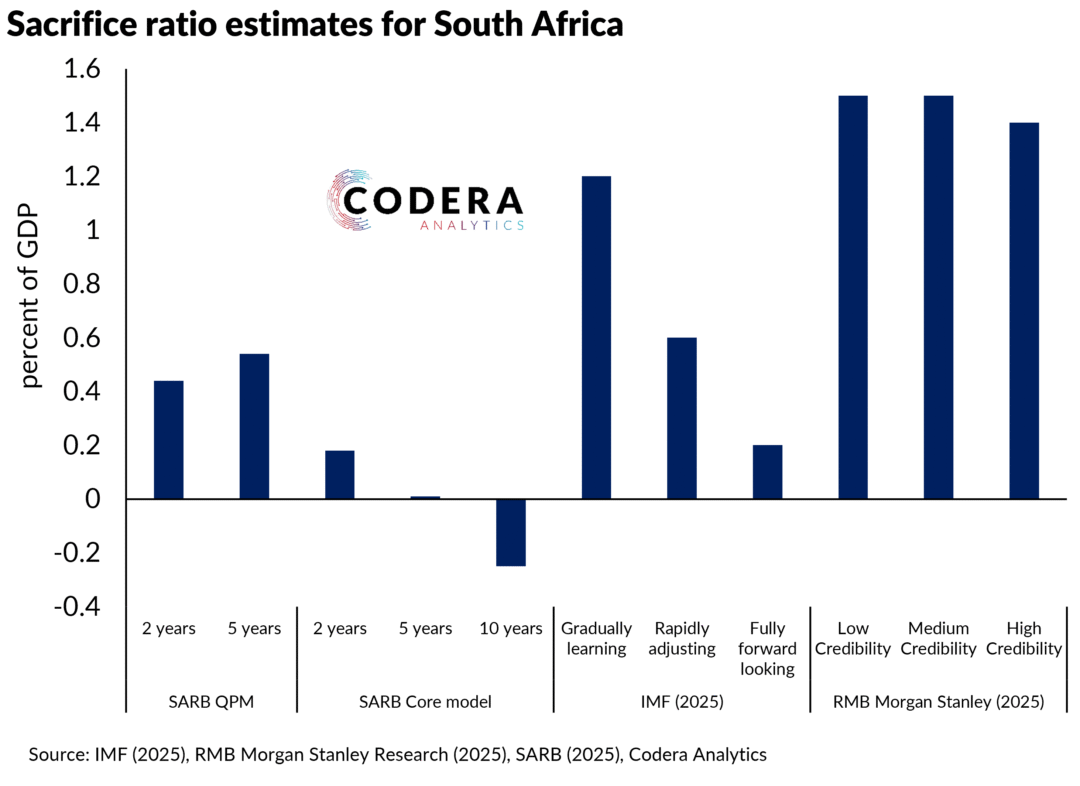

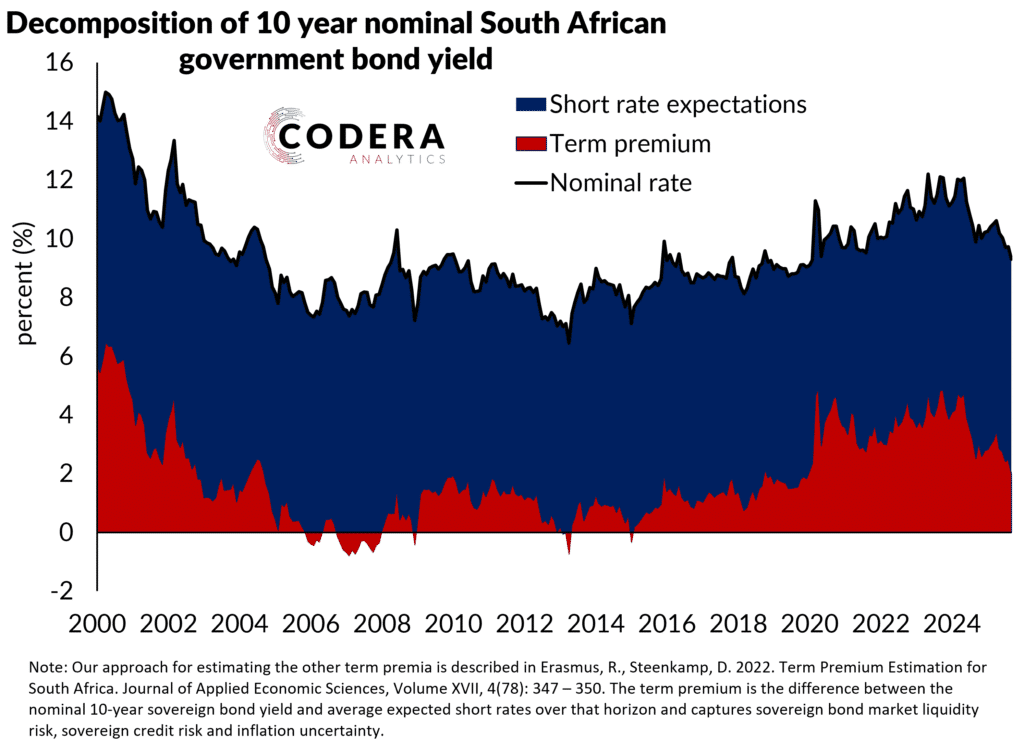

The transition costs of a lower target depend on how long the Bank will need to maintain a tight policy stance to drive inflation to the target. The long-term benefits depend on how much long-term borrowing costs fall after a shift to a lower target.

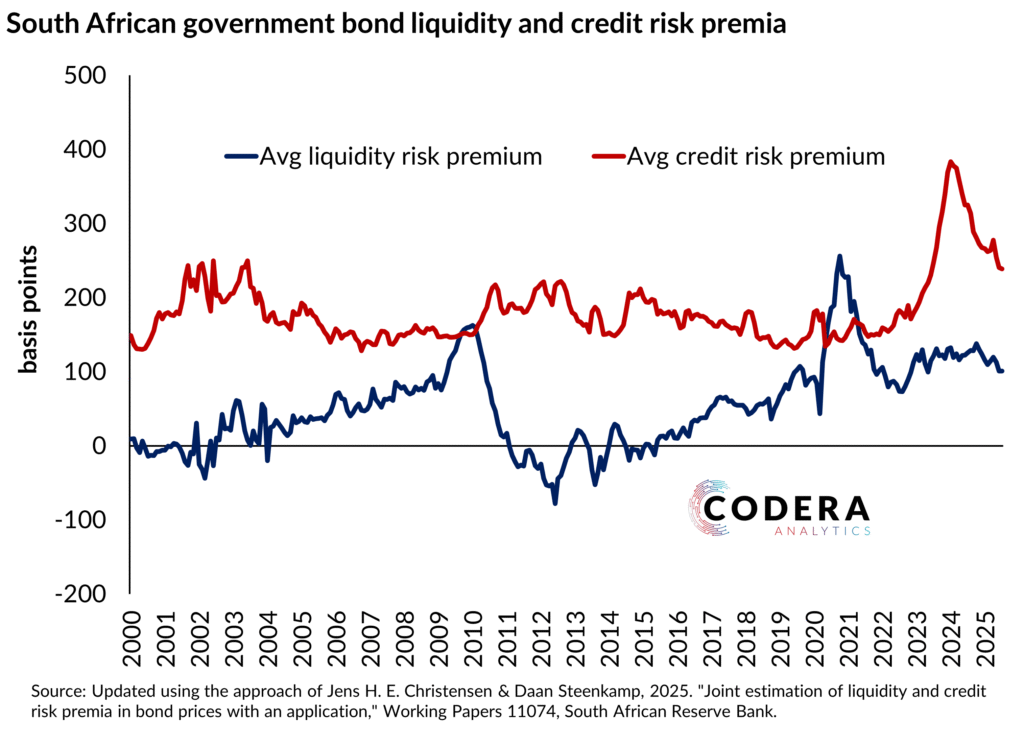

SA bond yields have fallen over recent months as the market has priced in a lower policy rate here and abroad and long-term inflation risk and inflation expectations have begun adjusting lower. But SA’s high long-term rates also reflect large credit and liquidity premiums, as our research shows.

Deterioration in the government’s credibility, or higher fiscal risks, would put upward pressure on borrowing costs despite a lower target. The government’s budget will be under pressure during the transition to a lower target from the divergence between expenditure and revenue growth. This is because many parts of government expenditure are fixed for the next few years (think of multiyear wage agreements for civil servants) and municipalities and state-owned enterprises are likely to require substantial support in future budgets (in the absence of public finance reforms).

A lower inflation target will also reduce the chance of using bracket creep (in which tax brackets are not fully adjusted for inflation) to buoy tax revenue growth despite slow economic growth. Government finances may make it harder for the Bank to achieve a lower target without higher interest rates.

As we argued in our paper about gaps in the inflation targeting debate, clear Reserve Bank communication is crucial to support reanchoring of expectations to a lower target. Poor households face higher average inflation and nearly five times more inflation volatility than the rich, given differences in inflation drivers (such as a larger weight on food for the poor). This creates a communication challenge for the Bank, given differences in the inflation experienced by different households and firms.

The same is true of supply-driven inflation. Supply shocks include droughts or storms that affect food prices, and these are an important driver of the inflation outlook in SA. The Bank must communicate its understanding of the structural factors that work against its disinflation efforts and explain how policy must address inertial price and wage settings.

There is also a risk to the Bank’s credibility if the Treasury does not agree to align the official target with the MPC’s preferred level. Co-ordination between fiscal and monetary policy is crucial for a successful transition to a lower target.

Without a government commitment to tackling high government-related inflation and reducing debt, the costs of transitioning to a lower target will be higher than the Bank assumes. It assumes for example electricity price inflation will average 3% in the long term.

As difficult as it will be to achieve, a social compact between the government, Reserve Bank, state-owned enterprises, regulators and labour unions would be the best way to achieve a low-cost transition.

Dr Steenkamp is CEO of Codera Analytics and a research fellow with the economics department at Stellenbosch University.